By Open Justice Multimedia Journalist Ric Stevens

Despite the recent spotlight on ram raids and smash-and-grab robberies, the number of young people ending up in court is dropping.

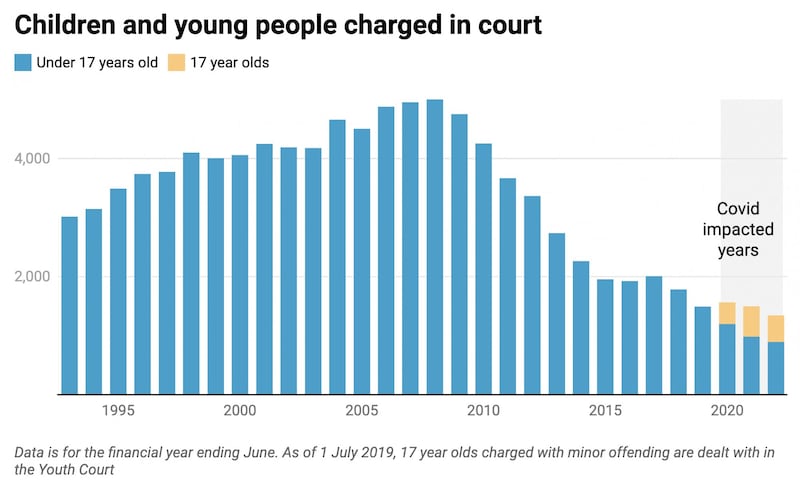

New statistics out today reveal just over 1300 young people aged 10 to 17 had charges finalised in court in the year to June 30, compared with 1500 in the previous year.

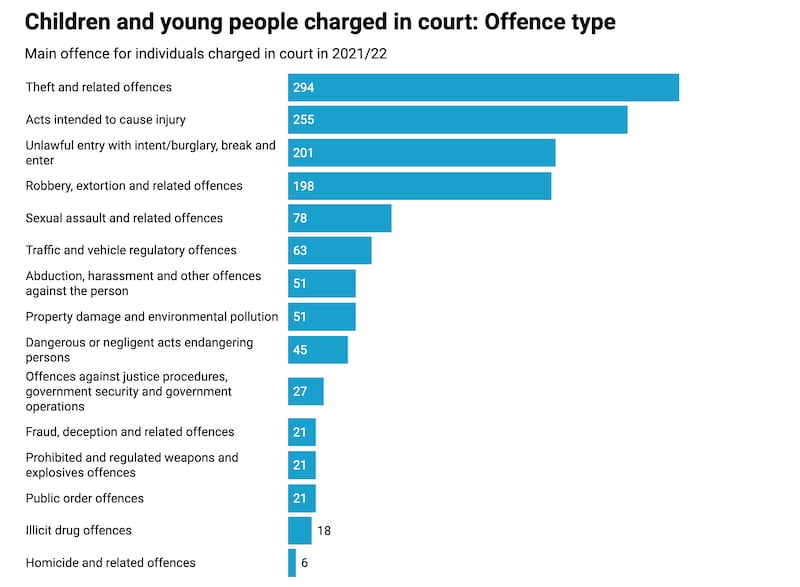

The most common crimes were theft, assault, burglary and robbery and the vast majority were male.

While the numbers reflect a downwards tend in recent years Māori remain disproportionately over-represented in the statistics – 63 per cent of those under 17 coming before the courts in the last year identified as Māori, compared with 26 per cent European, 7 per cent Pasifika and 1 per cent Asian.

The Justice Ministry said that the latest figures would have been impacted by the Covid-19 pandemic, and this should be borne in mind when considering trends.

For victims of crime the statistics might feel at odds with recent publicity about youth offending post-lockdown, especially in relation to crimes committed since July which won't be reflected in the data until next year.

Last month, Police Minister Chris Hipkins said there had been 129 ram raids committed since May, and almost all of them were done by people under 18. The median age of those identified or caught so far was 15 years old, he said.

But rather than being out of control, youth crime now is much lower now than it has been for decades. The number of children under 16 being charged is just a quarter of those facing the courts 20 years ago.

The Ministry of Justice figures show that the number of under-16s charged with an offence dropped by 10 per cent a year between 2017 and last year, and by 9 per cent in the year to June 2022.

Even with 17-year-olds added into the youth justice system, as they were three years ago, the youth courts are still catering for fewer young people than when they were dealing with only the under-16s in 2018-2019.

Chart / NZME

The decrease in youth offending is not unique to New Zealand – similar drops have been seen in England and Wales, Australia, Canada and the United States.

Exactly why is not well understood, although overseas studies have suggested everything might have helped from youth programmes which prevent people learning criminal behaviour, to more security systems in cars - preventing joyriding - which might be a gateway into more serious offending.

A report from Oranga Tamariki in 2020 suggested that a range of factors might be contributing to the trend in New Zealand, including changes in policing, increased levels of public security including CCTV, and more secure motor vehicles. It also suggested that anti-social behaviour might be moving away from the real world and on to the internet.

Another factor is that young offenders are more often dealt with by police outside the court system - by being given a warning, or by being referred to Police Youth Aid.

University of Canterbury sociologist and researcher in crime and justice Jarrod Gilbert said the youth justice figures could be seen against a background of a declining crime overall.

This was borne out by data points such as murder rates, which peaked in New Zealand in the late 1980s and 1990s.

"It could be that this is a good news story and New Zealand is becoming safer," he said.

The declines in young people before the courts were reflected across all ethnicities, although Māori remained over-represented.

There were 849 Māori tamariki and rangatahi before the courts last year, but this was down from 888 the previous year and more than 2000 a decade ago.

Principal Youth Court Judge John Walker told RNZ National's Morning Report earlier this year that young Māori offending rates were falling faster than for non-Māori, but "it still leaves us with a disproportionate number of Māori in our criminal justice system generally".

It reflected disproportionate figures for Māori in other indications like health, housing and poverty, he said.

"All of these things contribute to offending behaviour. This low number of young people appearing in our youth court really means that the number we are seeing are very complex young people with a myriad of complex issues underlying their offending behaviour.

"A lot of this falls disproportionately on to Māori - the neuro-disabilities, the exposure to trauma, brain injury, all these factors that we're seeing constantly in the youth court," Judge Walker said.

The challenge was to address the underlying causes early, he said.

Overall, the most common charges laid in the last year were for theft, assault, burglary and robbery.

Chart / NZME

A third of those charged were 17 years old. Twenty-four per cent were 16, 21 per cent were 15, 19 per cent were 14 and only 3 per cent – 36 children to be precise – were in the 10 to 13 age group.

Eighty-three per cent were boys and 17 per cent were girls.

When the 17-year-olds were excluded from the data, allowing direct comparison with previous years, it was found that there were 900 children and young people with charges finalised before the courts.

This was less than a quarter of the number being charged right through the 2000s – the number did not fall below 4000 between 2001-2002 and 2010-2011. It has been in a consistent decline ever since.

Children's Commissioner Judge Frances Eivers it was "excellent" to see this steady decrease.

"We are all concerned when we see what feels like outbreaks of offending, such as the recent ram raids, but there are very real signs of improvement," she said.

She said that at the core of this process was a combination of restorative justice pathways and prevention.

Solutions had been found in an "holistic" approach, where whānau and community – including iwi, police and other agencies – worked collaboratively to wrap support around youth and whānau who might be at risk.

"The focus needs to be on prevention to ensure the safety of these young people and the public, while restorative justice provides accountability, and healing for all involved," Judge Eivers said.

"Everyone in the lives of these children has a role to ensure they are safe, and that's about checking in on them and supporting them to make good decisions.

"If as a community we focus on preventing these things happening in the first place we can make a difference and are not left to pick up the pieces," Judge Eivers said.

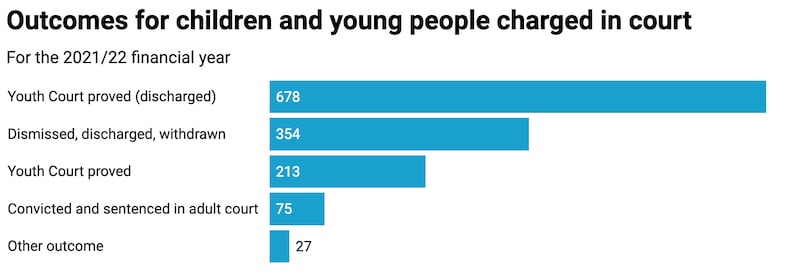

What happens in Youth Court?

At the end of the Youth Court process, children and young people usually receive an absolute discharge under Section 282 of the Oranga Tamariki Act. Usually, this means that the young person has admitted their offending and has taken part in programmes and interventions, such as drug and alcohol counselling, community work, paying reparation or observing curfews. A Section 282 absolute discharge wipes the slate clean, as if the young person was never charged.

Young people who commit more serious offences, or who do not stick to their rehabilitation plan, can be made subject to an order under Section 283 of the Oranga Tamariki Act – the equivalent of an adult sentence.

In the most serious of cases, young people may be transferred to the District or High Court, where adult sentences apply.

Chart / NZME