Photo / Supplied

By Kevin Norquay, Stuff

Kevin Norquay is meeting CEOs all over the country, getting their stories. This week, the final week of the series, he talks to Oranga Tamariki's Chappie Te Kani.

Being Oranga Tamariki chief executive is a tough gig; at one end a bad news cyclone, at the other a public wanting results. Yet Chappie Te Kani is all civil service with a smile as he evokes his past to move into the future.

Te Kani (Ngāti Porou, Te Aitanga a Māhaki, Tūhoe, Ngāti Maniapoto, Rongowhakaata) rises from a desk tucked away in a corner of the Oranga Tamariki head office, advancing with a grin and an extended hand.

In those hands lie the fate of thousands of children, for whom he is the statutory guardian, their protector. It is his job to ensure appropriate policies and practices for tamariki and rangatahi in the youth justice system, and those taken into care, unable to be cared for by whānau.

In December, he was confirmed chief executive after more than a year as acting CEO. While others might see a poisoned chalice, Te Kani sees opportunity.

He comes from a prominent Tairāwhiti whānau that has provided generations of social service, which brings him in with confidence, knowledge, and empathy.

Te Kani’s mother, former Māori Women’s Welfare League national president Jacqui Te Kani, pictured with foundation member Anne Delamere in 2011. Photo: Andrew Gorrie / Stuff

“I've never felt like I've had impostor syndrome. I've never had `oh, should I be doing this job?'. It's just part of my nature because everything I do is just totally committed to it,” he says.

“I won't step into a thing until I believe in my ability to do it. And I'm 150% committed to it. That belief … stems right back, from my mother, my grandmother, that resilience.

“My mum had this great line: ‘Just get over it, move on, keep going’, whenever you have a setback. No time to lie there and mope about it. Get up, carry on, learn from it, get on to the next thing.

“It happens every day here, you get bucked off the horse a lot here.”

Jacqui Te Kani, his mother, devoted her life to helping and leading. When she died in 2012 she was general manager of the Māori Women’s Welfare League and a past national president.

“I've come into the job with my eyes open, knowing it's going to be a challenge,” he says. “The reason I'm doing it, first it comes from my mum. I saw her working tirelessly for whānau in these situations.

“Fighting for them, just constantly believing in their ability, and for those whānau that were actually harming kids, standing in front of them saying 'no, the government's got a role here. I'm going to get them in here to keep those kids safe’. I saw that growing up.

"My mother has had a huge impact, to underscore it."

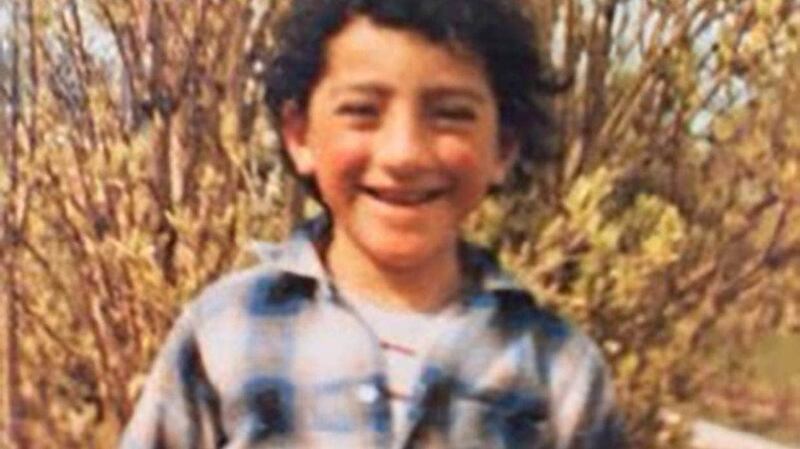

Oranga Tamariki CEO Chappie Te Kani when growing up in Gisborne in the 1980s. Photo / Supplied

His grandmother Joyce Hingatu Cairns helped raise him, while his widowed mother was away in Wellington earning to support the whānau, work that in 2001 saw her made a Companion of the New Zealand Order of Merit.

Growing up back in Ormond, on the outskirts of Gisborne, Chappie Te Kani was learning lessons he says remain with him to this day.

“We had lots of whānau in our house. In a formal sense, you wouldn't say it's fostering. You’d just have periods of people struggling; mum and dad, cousins. No money, no food,” he says.

“You would go through weeks of having them there to get back on their feet. And then they'll go somewhere else. So that was normal for us, whether it was my grandmother or my mother, we were always looking after people.

"It just was the natural thing to do. So for me, I have got that built in me for what I want to do in this role. I came in knowing all the tensions and criticisms and pressure that's gonna be on the role. So I'm doing this with my eyes wide open, I fundamentally believe in my ability to make a difference. Like, fundamentally."

Chappie Te Kani grew up on a farm. Photo / Supplied

Let’s address that name, Chappie. Officially, his name is Te Hapimana. Chappie is another thing passed on by his whānau, along with his sense of service. Te Hapimana Chappie was his Tūhoe grandfather’s nickname.

He grew up on a farm at Whatatutu, a small town northeast of Gisborne, cut off when Cyclone Gabrielle washed away an access bridge, but largely unaffected thanks to it moving its low-lying marae and schools post Cyclone Bola in 1988.

While his father and grandmother were native speakers, young Te Kani never learned, as te reo was banned at school. Regrets, he has a few.

“Of course. But seeing it now, in this generation, the revitalisation, the passion, the love this generation have for te reo is amazing, and not just Māori but Pākehā as well,” he says.

Nor was he aware of racism in those blissful days among the farm animals, crutching and shearing sheep and developing an enduring love of horses.

“It was a Māori-Pākehā farming community - everybody was committed to the community, so hard working. It didn't matter what race you were, you just supported each other. And that's the value that was installed in us, right from the get go.”

Chappie Te Kani with Prime Minister’s Oranga Tamariki award recipient Jonah Shortland. Photo / Supplied

His father, who died when Te Kani, the youngest of four, was 8, was known as a horse whisperer.

“He was magic with horses, I could ride a horse before I could talk or walk. I haven't been on a horse for a very long time… but I still love horses. Every time I see a horse I gravitate to it.

“I can talk to a horse - not talk to it - but calm it down. If I see a horse that I don't know, I can go up to it, know how to communicate with it, horses are incredibly communicative.”

After primary school, he went to Waikohu College in recently weather-smashed Te Karaka, then to Gisborne Boys’ High, where he was a good student and an “over confident” 1st XV midfield back.

“I wasn't the head boy or rugby captain. Gizzy Boys was very horizontal. Think about the most relaxed school you can imagine. At assembly they'd read out the surf report. At 11 or 12 you'd go surfing.”

Post Victoria University, his civil service career started as deputy secretary of treaty negotiations with the Ministry for the Environment in 2008, and spans time as a policy adviser in the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, under John Key.

Malachi Subecz, 5, died in Starship Hospital on November 12, 2021. Te Kani publicly apologised to the family. Photo / Supplied

Which leads us back to Oranga Tamariki, and a job Te Kani says the Public Service Commissioner rates the most difficult in the public sector.

“New Zealand expects you to keep every kid safe. And particularly our communities want me - the state - to have less of a role in their lives. Everybody gets that.

“And you see the tension, it's a near impossible Rubik's Cube to solve. And you're always having to manage that, then you've got a public who don't want failure.

“Whoever sits in this role - whether my predecessors or whoever comes after me - they're going to have to manage all those tensions.”

But no news is good news in his eyes, and he points out after a period of turmoil, Oranga Tamariki has avoided the headlines, as well as fronting when it has got it wrong.

Oranga Tamariki investigated its practices in the months before the 2021 murder of 5-year-old Malachi Subecz by caregiver Michaela Barriball.

When the review was released, Te Kani apologised to the family, promising improvement and outlining “how we will do better”.

He directed that only social workers with more than a year’s experience should undertake initial assessments.

“There was a period there where Oranga Tamariki was in the media every day, with criticism. You'd struggle to see us there once a month now,” Te Kani says.

“Even at our peak when we had the sad death of Malachi we managed to own what we did, demonstrate accountability and then give us the space to work on what we need to do to fix it.

“New Zealand is genuinely acknowledging our attempt to show accountability. That's what I believe.”

Te Kani does not see himself as a helicopter view CEO, in an office above the fray. While he was acting he visited all frontline staff, he says. Kids, too, and caregivers, social workers.

“I was right at the coalface, skipped right over all the middle management, meeting, talking, touching, seeing what we do every day, and I did it for all our sites around the country.

“That orients my leadership so I talk about that - everything we do here has to make a difference for our staff out there doing the work. And if it doesn't do that, then we don't do it.

“We've also got, in my view, the best conditions for success that I think we've ever had. We've got resources. We are building confidence with the public now.”

Part of his deal is rebuilding the confidence of his staff to share the good stories, when they happen.

Chappie Te Kani plans a return to Gisborne when his working days are over. Photo / Supplied

“We are a humble organisation, it's very hard to get people to talk about the good work that we do. Very hard, very hard,” he says.

“They feel very anxious talking about the good news story, putting their head above the parapet, in an organisation that over the years - and I'm not saying it was wrong - has always been criticised.

“There's a mindset [of] ‘we open our mouth, we get criticised.’”

Ideally, there would be no children in state care. That’s impossible, Te Kani says. Fewer, though – that can be done.

“The state shouldn't be the parent of our kids in Aotearoa. I firmly believe that, but we will have a role for those tamariki that I see that have suffered physical, sexual, neglect.

“There's just no other route for them, but for us to intervene to keep them safe, to remove them from the care. But that's not 4800 kids, it's a smaller number.

“All tamariki that are in care, they're here for a reason. And they've got a number of conditions and lots of trauma.”

And what about him? How does he cope with the scale of the problem, one which by his admission can never be solved? It is a mental strain, surely?

At those troubled times, Te Kani goes back to his core. He might even seek out rural Gisborne, a place he intends to return to once his working days are over.

“My whānau, my whakapapa … my absolute core is my identity, without hesitation, I was born Ngāti Porou, I will die Ngāti Porou, and everything in between is part of my journey.

“I know where my maunga is, I know where my land is, I know my whakapapa, that is my core, that's my compass. If I ever feel I'm losing perspective, I get back to my core - my wife and my kids.”