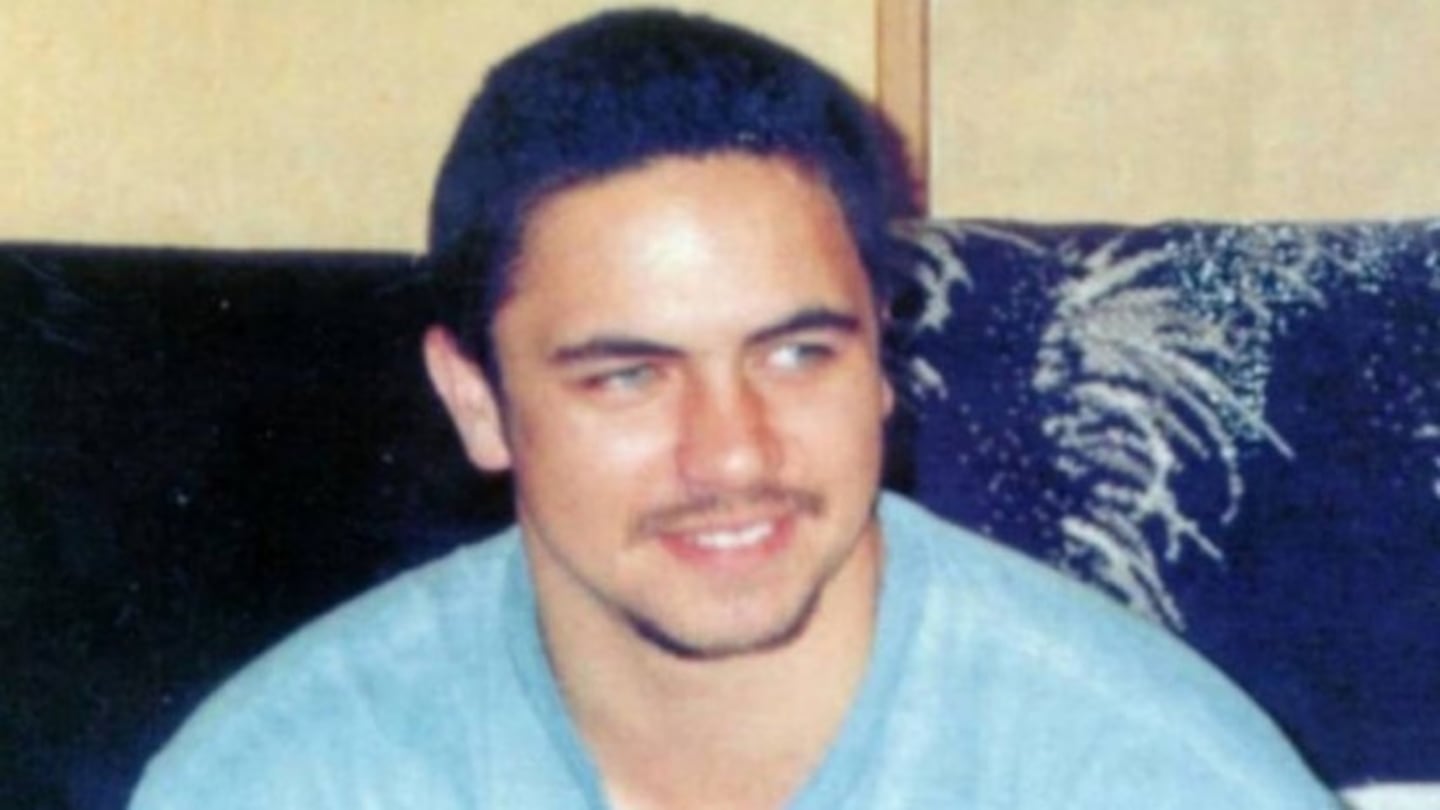

Steven Wallace was fatally shot by police in 2000. Photo / RNZ

After her decades-long battle to hold police accountable for the fatal shooting of her son, a “very disappointed” Raewyn Wallace has reached the end of the road.

A Supreme Court decision refusing to hear her case has concluded the anguished mother’s long journey before multiple courts in the name of her son, Steven Wallace.

“There is no other legal option for Raewyn,” her lawyer Graeme Minchin told NZME on Wednesday. “There’s nothing that can be done.”

Minchin, who has worked on the case for the past 10 years, agreeing to only take payment on a “results” basis, spoke with her after the decision was released on Tuesday.

“She’s very disappointed. She’s not happy,” he said.

“It’s incredible what she’s done. She’s been the driver of this, well Jim [Wallace’s father] as well, until he passed away.

“It’s been a very long road for her. It’s very tragic for her. She lost her beloved son and that’s what’s been behind it all.”

Minchin said that while upset by the decision, Raewyn, who NZME could not reach for comment, understood there was no other legal recourse.

“We took it to the end of the road [...] for her, she’s done everything she could. It doesn’t bring her son back but she’s done everything that you could possibly do.”

Wallace was 23 when he was shot in the early hours of April 30, 2000, on the main street of Waitara, Taranaki. He died in hospital a short time later.

He had been on a rampage, breaking windows with a golf club and attacking a patrol car with officers in it when he was confronted by police. Senior Constable Keith Abbott shot him four times. One penetrated his liver, fatally wounding him.

Twenty-three years and a string of legal proceedings later, the Supreme Court, the final appeal court of New Zealand, has now dismissed an application by Raewyn to challenge a civil ruling related to his death.

While the court agreed the state’s obligation to investigate the fatal shooting of Wallace was an important matter, it was not satisfied the proposed appeal had sufficient merit to warrant the grant of leave.

Raewyn commenced civil proceedings against the Crown in 2014, alleging a breach of her son’s right to life under the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act 1990. Declarations were sought together with compensation.

This followed a failed private prosecution of Abbott by the Wallace whānau who charged him with murder after the police did not. In December 2002, a Wellington jury acquitted the officer, who claimed he shot Wallace in self-defence.

The civil claim was finally heard in the High Court in 2020 and ultimately upheld that Abbott had acted in self-defence.

But the court also found the investigation into Wallace’s death had not been compliant with the Bill of Rights and that the Solicitor-General failed to give adequate reasons for refusing to take over the private prosecution.

While declarations in respect of those two matters were made, no damages were awarded and the claim was otherwise dismissed.

Raewyn then turned to the Court of Appeal in an attempt to challenge the High Court’s ruling on the issue of self-defence, and the Crown cross-appealed the two findings in her favour.

In a double blow, the Court of Appeal rejected her appeal and further ruled in the Crown’s favour, overturning her previous wins.

The latest proceeding saw Raewyn apply to the Supreme Court, proposing 13 grounds of appeal that challenged the Court of Appeal’s findings of law and fact.

Justices Ellen France, Joe Williams and Stephen Kos found only three of those raised questions of general importance.

Those were around self-defence in a civil context, the reverse onus in claims made under the right not to be deprived of life, and whether a private prosecution satisfied the Bill of Rights’ obligation to investigate.

However, in dismissing the appeal, the judges stated they were not satisfied the case was an appropriate one in which to address issues of principle.

They found most of Raewyn’s remaining proposed grounds were case and fact specific.

“...and they are unsuitable for consideration on a second appeal due to the constrained evidential and procedural basis upon which the case has proceeded,” the decision said.

Raewyn had argued that prosecution in the earlier trial of Abbott was under-resourced causing counsel to wrongly adopt an overly narrow approach, which the judges rejected.

“We are not satisfied that there is a proper evidential basis upon which the required inferences might be considered arguable,” the decision said.

“As to the Solicitor-General’s failure to provide reasons for refusing to take over the prosecution, the Court of Appeal’s decision related to a straightforward matter of procedure which arose in the distinctive procedural history of this case.

“No question of public importance is involved and we are not satisfied that there is any risk of miscarriage if leave is not granted on this ground.”

While Minchin doesn’t agree with the decision, he accepted nothing more could be done.

He said the early criminal prosecution had “thrown a long shadow” over the civil proceedings.

“The attitude has been ‘that’s gold-standard’. You’ve got a High Court criminal murder trial and it came with these findings.

“What we say is that it was always an unequal contest, just in terms of money, and that there were very serious errors that were made by trial counsel.”

But Minchin failed to get those claims across to the Court of Appeal, he said.

He said the Wallace whānau funded the prosecution by way of sausage sizzles and selling hāngī.