A bust of Ngāti Toa tupuna Wi Neera Te Kanae was welcomed back to the Takapūwāhia Marae. Bruce Mackay / The Post

By Justin Wong, Stuff

Known only as A01392 in the records of a German museum, now the life mask of a Ngāti Toa tupuna has returned to his whenua and people as a taonga. Justin Wong reports.

Under the blue sky on a chilly Wednesday afternoon, a karanga rings out at Takapūwāhia Marae as a pōwhiri begins to welcome an ancestor returning home.

A procession of people walk slowly towards the wharenui, behind two kaumātua, one of them carrying a white box. Inside the box is a 70cm-tall coloured bust of a man on a stand. The man’s eyes are closed, but he has an impressive goatee. “Maori [sic]”, “New Zealand”, “Man”, the label on the stand reads in German.

This is the resemblance of Wi Neera Te Kanae, a great-grandson of prominent Ngāti Toa rangatira Te Rauparaha and a grandson of Te Kanae, another Ngāti Toa ariki (paramount chief). He was a significant and prominent leader of the iwi during the late 19th century, and became a Native Land Court assessor in 1884.

Ninety-year-old Mahurenga Wi Neera, the eldest male of Ngāti Toa Rangatira and the closest descendant to Wi Neera Te Kanae, held on to the box that carried the cast of his grandfather at the head of the procession with 93-year-old Karanga Metekingi, the iwi’s matriarch and the oldest living descendant of Te Rauparaha.

Other whānau – also direct descendants of Wi Neera Te Kanae – held up pictures of other ancestors as they followed the kaumātua into the wharenui.

It was a solemn but proud occasion for the iwi, said Dr Taku Parai, the Pou Tikanga of Te Rūnanga o Toa Rangatira and a great-great-grandson of Wi Neera Te Kanae.

“Most of the iwi from Takapūwāhia come from him,” he said the day before the pōwhiri. “We as a people agreed that we need to treat it as such, that he is coming home to his people, to where he belongs, to his whenua.

“It [the bust] looks like him. It feels of him. His wairua [spirit] was a part of that.”

Dr Taku Parai, Pou Tikanga of Te Rūnanga o Toa Rangatira, said the people agreed to welcome the bust as if Te Kanae is coming home. Monique Ford / The Post

For more than a century, no one from Ngāti Toa was aware of the bust’s existence, which was made off a life mask by German ornithologist and ethnologist Otto Finsch – it was hidden away in the archives of the State Ethnographic Collections Saxony in the east of Germany, numbered as A01392 in the records.

It was about a month before the repatriation of more than 100 Māori and Moriori remains and other taonga from seven German institutions to Te Papa that Parai was told of the bust’s existence through an email.

“I was hugely astounded,” he said. “It was quite a surprise that they had one of these. We would have went there straight away and brought him home.”

Direct descendants of Te Kanae welcomed back their ancestor on Wednesday. Bruce Mackay / The Post

Among the people at the pōwhiri were the institution’s director, Léontine Meijer-van Mensch, its Oceania collection’s curator, Dr Birgit Scheps-Bretschnider and her partner, Christoph, who came to New Zealand for the occasion.

The repatriation had been a learning experience.

“When we were working about the provenance, we very quickly found out that we are not only talking about ancestral bones, but also talking about objects that have a spiritual life – this bust is an example for them,” Scheps-Bretschnider said.

“That was a [new] step in the museums’ world in Europe to think about objects with its own spirit.”

Dr Birgit Scheps-Bretschnider, left, the curator of the Oceania collection at the State Ethnographic Collections Saxony, and the museum’s director Leontine Meijer-van Mensch, right, are in New Zealand to make sure the taonga is returned. Juan Zarama Perini / The Post

A01392

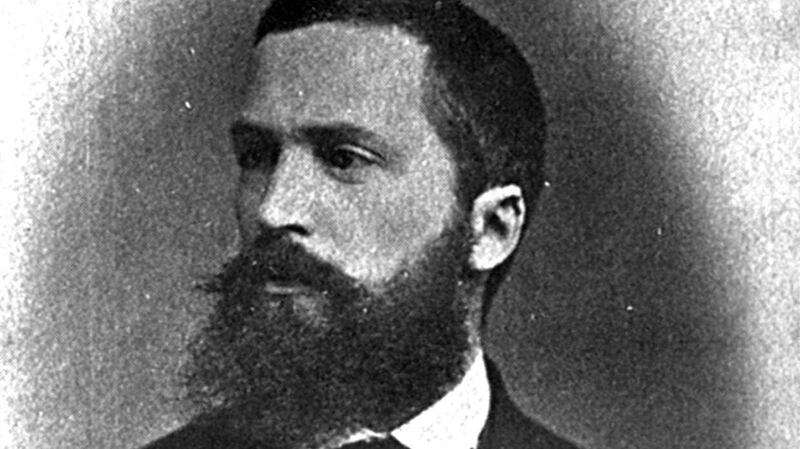

Before setting off on a three-year funded expedition in the Pacific in 1879, Otto Finsch was already an active collector, but he was more interested in natural history specimens than making a plaster cast of a person’s face.

It was German anthropologist Rudolf Virchow who instructed Finsch to also make life casts of indigenous people during his travels, said Australian National University’s Dr Hilary Howes, who researched European science in the Pacific and wrote about Finsch.

“It was thought at the time they were a more reliable way of capturing information about a person’s face or other body parts,” she said. “It was three-dimensional ... [it could] capture more information about that person than a sketch, or photograph or just a series of measurements.”

Mahurenga Wi Neera, left, who is the eldest male of Ngāti Toa Rangatira and the closest descendant to Wi Neera Te Kanae, held on to the box carrying his grandfather’s bust. He led other whānau members into the wharenui with 93-year-old Karanga Metekingi, the iwi’s matriarch. Bruce Mackay / The Post

Making plaster life masks was relatively new at that time, but Howes said there were manuals available. The subjects would have their facial hair and eyebrows greased up before applying the plaster. They would then have to lie flat for 40 minutes as it dried.

“We don’t know what it was like for the people who are actually having their faces cast, but we know Finsch said it was an unpleasant process,” she said. “He was surprised that he had been able to convince people to do it.”

In fact, finding Māori to make life masks was so difficult in Aotearoa, Finsch had to call in a favour.

“My eventual success ... is only due to the mediation of my friend [later Sir] Dr W [Walter] Buller in Wellington,” Finsch wrote after returning to Germany. “It was only out of friendship and respect for him that several natives eventually allowed themselves to be persuaded to undergo this not very pleasant process.”

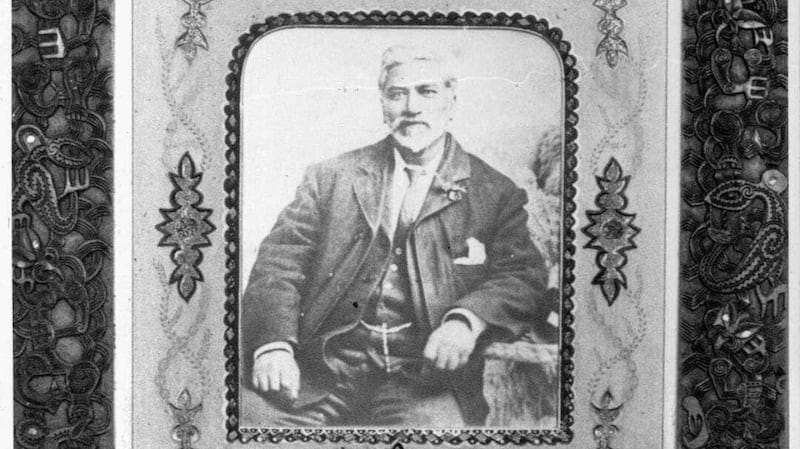

Ngāti Toa Rangatira tūpuna Wi Neera Te Kane. Ref: 1/2-135551-F. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. Source / Alexander Turnbull Library

Finsch made over 200 casts of indigenous people’s faces and body parts throughout the expedition.

But only 164, including four life casts of Māori, made it back to Europe because a ship caught fire and sank in the Torres Strait.

Finsch kept the property rights to the life masks, and commissioned a Berlin wax museum to make coloured copies of them to be sold to museums and institutions. He even published a detailed 78-page catalogue about the masks, documenting the person’s approximate age and personality.

“Wiremu Nera [sic] te Kanae chief of the Ngatitoa tribe of Porirua, province of Wellington,” the catalogue wrote. “A large powerful man of about 34 years of age, and a beautiful type of Maori. He is the grandson [sic] of the celebrated warrior Te Rauparaha.”

The anthropology museum in Dresden purchased a copy of several casts in 1900, including that of Te Kanae. It was recorded as A01392 and put on display. Others bought copies for research.

German ethnographer Otto Finsch made the life mask of Wi Neera Te Kanae. Supplied / Stuff

Scheps-Bretschnider and Howes said the masks were less about the depicted individual but more about categorising people based on appearances.

“They used this cast to exhibit the ‘exotic person’,” said Scheps-Bretschnider. “They were combined with the skeletons [or] portraits, and it should give you the image that they look different.”

“The cast wasn’t made to depict an individual,” Howes said. “They were made to depict a racial type, so museums could have this series of casts and say, ‘this is what a Māori looks like’. This generalising impulse had the effect of wiping away a lot of the personal details that would be the most important thing about casts like that.”

And there could be other casts of Te Kanae in museums around the world, Howes said, as five museums in Australia and Europe bought Finsch’s full mask collection and other institutions also made smaller selections throughout the years.

“This one that’s returned home is not the only one in existence.”

Sitting amongst the ancestors

Back at Takapūwāhia, Ngāti Toa celebrated their tupuna’s homecoming throughout the day with kapa haka, kai and kōrero about stories and whakapapa.

The following morning, Te Kanae’s bust was moved from the marae to Pātaka museum in the city centre – this time not to a dark corner of the archive, but a place at the Whiti Te Rā exhibition about his iwi and close to Tuhiwai, the famous mere pounamu wielded by his great-grandfather.

“We’ll set [him] out besides his peers, his ancestors and with all that taonga,” Parai said. “He’ll be comfortable there. We have an opportunity for our ancestor to be back with his people and sit with our other taonga and treasures that we have.”

The story would also be a good platform for rangatahi who were interested in their ancestor’s journey, or who wanted to do research about why people wanted to do life casts of others in the southernmost part of the world, he also said.

Mahurenga Wi Neera, left, and his wife Lois Wi Neera, right. Bruce Mackay / The Post

But in the long term, the iwi is planning to build its own museum to bring all of its taonga back home.

Léontine Meijer-van Mensch, the Saxony state collection’s director, said the repatriation was the beginning of a new chapter in their relationship with mana whenua. Further plans to return more taonga Māori, such as pounamu, were already under way.

“It’s important to tell these stories which this museum played a party to and of taking responsibility,” she said. “It is one of the most important tasks as a museum and that will take generations of museum directors and professionals.

“I think we can’t completely decolonise ourselves as European museums but we can constantly reflect on that process.”