In the war to save te reo, was the first casualty our skill for giving each other shit? Reporter Joel Maxwell speaks to a Māori author helping us speak from the gut, not the brain.

We’re all victims of the English language to some extent.

For a while in Hona Black’s life, he was lucky enough to hear only the faint echo of English. His quarantine, which filtered out even Pākehā music, lasted till he was about 11. Growing up in te reo Māori was a spell of freedom in a country that has a crushing case of the monolinguals.

To speak two languages in Aotearoa, he says, needs staunchness – but it’s as simple as making the choice to be the master of your own home.

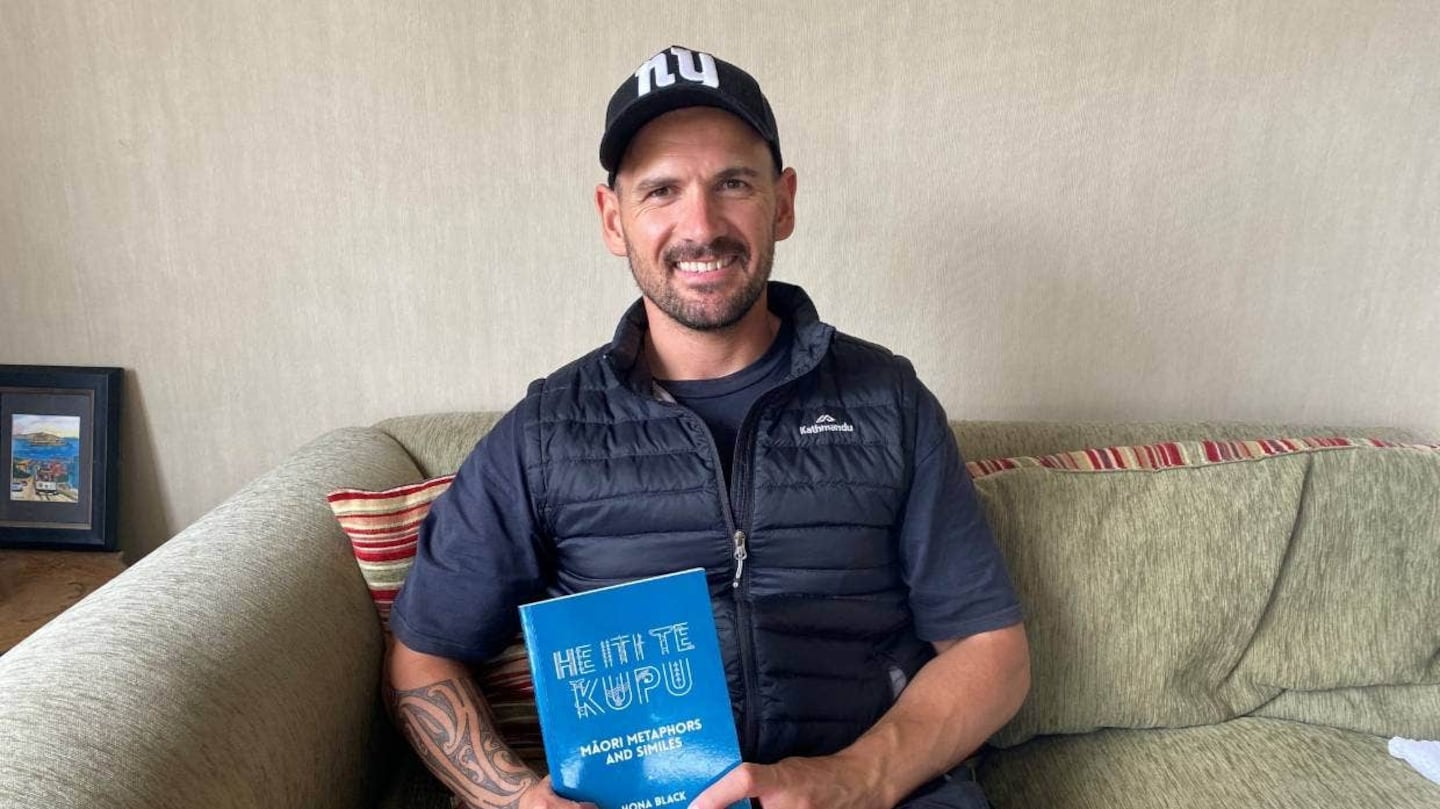

Black, 33, an author and Massey University senior lecturer in Māori knowledge, spoke to Stuff about his latest book, Te Reo Kapekape: Māori Wit and Humour. It is a resource for reo speakers of all levels that seeks to overcome the greatest challenge in any language: getting a laugh out of its communal audience.

The book came after a kōrero with a kuia, who said the language had changed. “She was talking about, in her time when they spoke te reo Māori, often the language came from the gut… These days people tend to intellectualise the language.”

He mulled this, then started writing about te reo kapekape – “the language of banter – being cheeky – in an attempt to entice a response”; Māori humour captured through more than 130 te reo phrases, translated to English, to describe people, events and actions.

JM: Tērā pea, whāki mai mō te tikanga o tēnei kupu ‘kapekape’, i roto i tēnei horopaki.

HB: Ko te kapekape, he whiu i te kupu, hei whakatoi, hei taunu i te tangata, otirā, i runga i tō hiahia kia whakahoki kōrero mai i te tangata rā.

JM: Kua pēhea koe e whai ana i ēnei kīanga, kupu, kōrero kapekape [rānei] – nā wai i tuku ēnei kupu, ēnei kōrero ki a koe?

HB: Ko te nuinga o ēnei kupu i rongo au mai i te wā e tamariki ana tae noa ki ēnei rā tata nei. Ka rongo noa i tētahi rerenga hatakēhi, ka whakaaro au ‘e, pai tēnā’ – ‘that’s a good one’ – ka tuhi au ki tāku waea, a, i roto i te wā, ka kuhuna atu ki te pukapuka.

Black heard quips and jokes from childhood till adulthood. Over time, it got easier to save the great material – he’d write hardcase things on his cellphone that he’d heard, and eventually they ended up in the book.

If you sit amongst older people who have spoken te reo Māori for a long time, they always inject humour into their language, Black said. In the younger generations it seems to be a bit of a lost art.

“I don’t think they really know how to get cheeky to each other in Māori, or have a bit of banter. If anything this book is an attempt to reposition this … as a language that’s really important.”

The colour, the fire, the laughs – a language spoken from the gut – compiled in the book come alongside a painful scarcity of reo Māori, of any kind, in everyday life in Aotearoa.

According to 2021 research, He Ara Poutama mō te reo Māori (by Nicholson Consulting and Kōtātā Insight), only about 1.5% of the total population were fluent speakers of te reo. That’s roughly one in every 100 people in the language’s homeland. About 8% of the Māori population were fluent speakers. Of these, the biggest single age group was those aged 9 and under.

Now, more than ever, it seems there is a need for resources that teach Māori to give each other a more hilarious ribbing in their native tongue.

Black’s first decade came with opportunities galore to absorb the language with his parents, Taiarahia and Shelley Black.

“I pretty much grew up only speaking te reo Māori, my dad was pretty staunch.” Actually, his mum was, too – she was Pākehā, but learnt the language herself, so she could speak it to her son.

Black didn’t start formally learning English till he was about 11 or 12 years old. “We would go from home to kōhanga, back to home and then on to kura kaupapa [school].”

The family’s circle of friends, “everyone we hung around with”, only spoke Māori. “It was a bit of a bubble.”

He grew up in Palmerston North, attending Te Kōhanga Reo o Te Āwhina, then he went on to Te Kura Kaupapa Māori o Manawatū.

As he got older he started navigating both worlds – knowing when to speak only Māori, and when to speak English.

“Because the English world is all around us, you can’t help but eventually have to engage with it; if you play sports and make a rep team, it’s not as if the coaches speak Māori or anything.”

Black says his dad grew up in a Māori-speaking family in Ruātoki, Tūhoe country. “They were pretty staunch in terms of when you come into the house, you only speak Māori.”

He feels lucky to have had that upbringing himself, or at least he does now. “It was so strict, we weren’t even allowed to listen to English music.”

Black started writing Te Reo Kapekape at the beginning of 2022, and completed it about 18 months later. It came on the heels of his book, He Iti te Kupu: Māori Metaphors and Similes, released in 2021.

He said there’s no doubt the two languages – Māori and Pākehā – inevitably interfere with each other for speakers, including himself, despite his upbringing in te reo.

When it comes to achieving authentic Māori patterns of speaking, nothing beats being around people who speak Māori all the time. Otherwise, cool phrases can gather dust for want of use.

“We could learn a really cool kīwaha [colloquialism], and we could be waiting months and months – or years – waiting for the perfect moment to drop that kīwaha.”

The opportunities to drop those verbal bombs increase if you have people to speak to in te reo, he says, so find a community of people with whom to speak Māori.

Black and his partner Rachel now have an 8-month-old son, who has started kōhanga – another generation will continue the whānau and Tūhoe tradition of immersion in te reo.

He says that in the end, no matter what language is spoken in the wider community, no matter the outside influences, you have total control over what language is spoken in your home. That was one of the big things in Ruātoki “back in those days”. Kids might get punished for speaking te reo outside, but they always spoke it within their own four walls.

“You have control of what happens in your house. So If you want te reo Māori to live in it, then that’s all it is: a choice.”

– A translation of the reo Māori section of this story is incorporated in the English section.