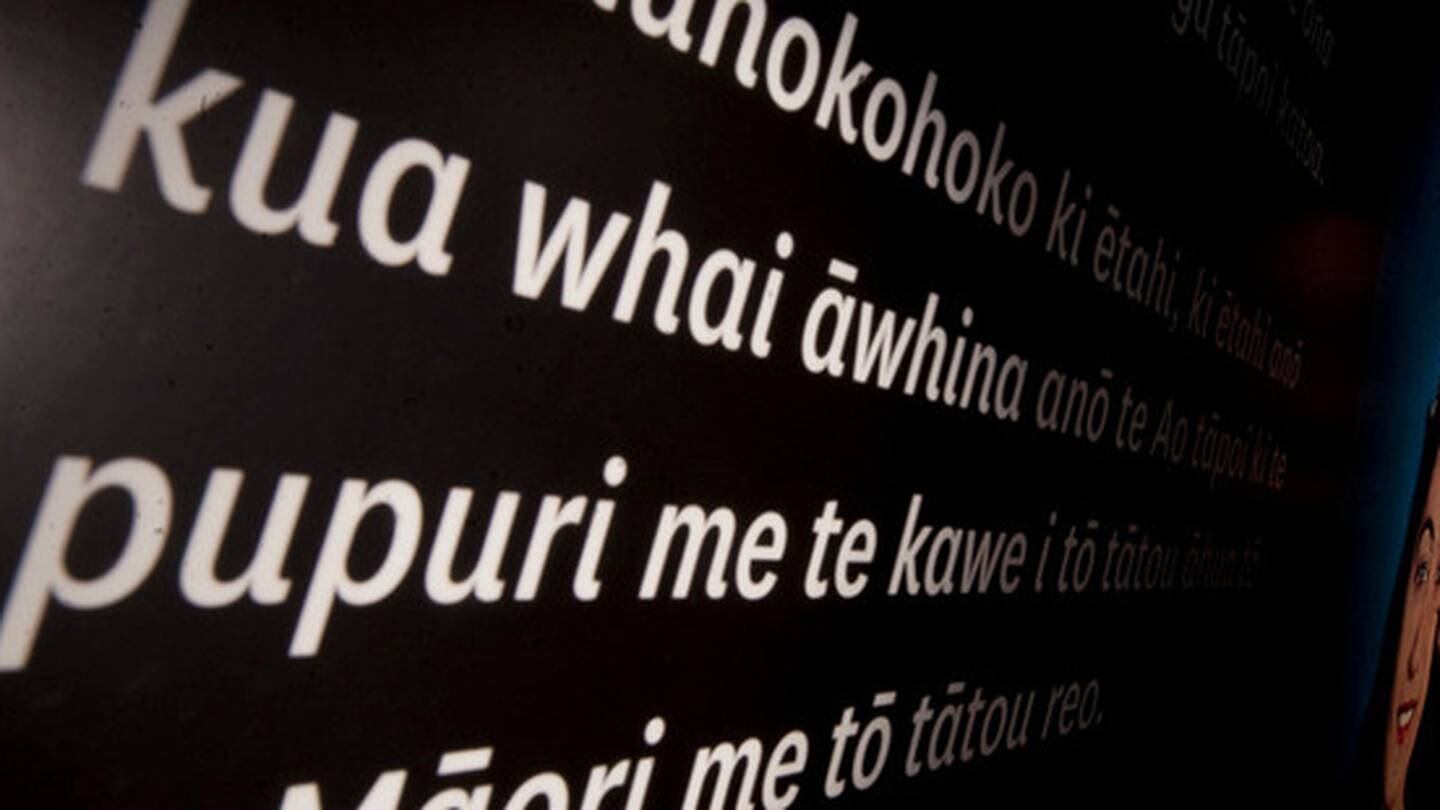

Early childhood educators in English-speaking centres play a pivotal role in preserving te reo Māori, and need more support to accelerate language uptake, a study from the Ōtākou Whakaihu Waka (University of Otago) has found.

The study, published in the Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand, found that the highest rates of te reo Māori were observed during kai time, book time, and group time routines. However, single words in te reo Māori (for example, “Are you ready for your kai?”) were used more often in comparison to two and three or more words in te reo Māori.

“These simple words are a positive first step, as they provide a foundation for more complex language use,” lead author Yvonne Awhina Mitchell (Ngāti Awa, Ngāi Te Rangi) said.

Co-author Dr Amanda Clifford said the study found use of te reo Māori was mostly led by the teachers, rather than tamariki.

“Language development during early childhood is dependent on rich interactions with adults, so these findings not only support revitalisation efforts but are also in line with the national early childhood curriculum, Te Whāriki,” she said.

The government’s Māori language strategy has set a goal for one million New Zealanders to speak basic Māori by 2040. Currently, 2.7 percent of people are able to hold a basic conversation, that’s around 140,000 people.

In the latest data, almost a quarter (23 per cent) of Māori said they spoke te reo Māori as one of their first languages, up from 17 per cent in 2018.

Teachers’ self-reported proficiency in te reo Māori varied from ‘beginner’ to ‘intermediate,’ underscoring the importance of ongoing support for kaiako, Clifford (Waitaha, Kāi Tahu, Kāti Māmoe) says.

“For some, accessing resources, training, structured support and ongoing professional development opportunities may enable them to better develop their language skills to incorporate te reo Māori into their teaching.”

Mitchell suggests such interventions would facilitate and promote increased use of te reo Māori, thereby normalising use of the language at tamariki age.

“There is an opportunity for more elaborate te reo Māori use in early childhood settings and language efforts should focus on how to shift speakers from simple phrases to the next level of language proficiency,” she says.

The researchers are working on a programme to enhance interactions between educators and tamariki through (among other things), the integration of bilingual books in the ECE centres where the original study was conducted.