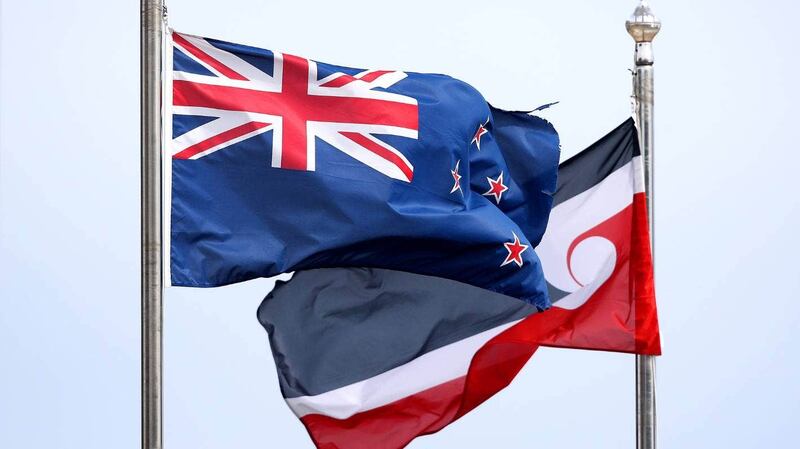

It’s been 188 years since He Whakaputanga o Te Rangatiratanga o Nu Tirene – the first founding document of Aotearoa was signed – but what does it mean today? Professor Margaret Mutu, whose tīpuna signed the document, spoke with reporter Maxine Jacobs about the history of the Declaration of Independence and its relevance today.

Hapū and iwi have responsibility for te taiao (the environment) and the people who live in Aotearoa, both Māori and Pākehā alike, says Professor Margaret Mutu.

“Pākehā, they are our manuhiri [visitors], and they will always be our manuhiri. And if your manuhiri are not looked after, then it’s your mana that’s impacted.”

But what happens when the leaders of the manuhiri start taking advantage of your hospitality?

Way back in the early 1800s, when northern iwi started to become concerned about the “lawless traders” arriving on their shores, rangatira (chiefs) were in constant wānanga (discussions) over how to deal with the antics of these foreign people.

Mutu (Ngāti Kahu, Te Rarawa, Ngāti Whātua, Scotland) who is an expert on the constitutional makeup of Aotearoa, says the laws that rangatira had on their lands were simple, and while there were differences across hapū, they were largely consistent with each other.

However, according to Mutu’s kaumātua, who heard it from their kaumātua, these tāngata hou, new people, didn’t understand – or chose not to – respect the ture (laws) of the place they knew as Nu Tirene.

Theft and murder were rife, she says.

“They were disgraceful, absolutely disgusting what they were doing, and the concern about that started spreading.”

The missionaries were OK, says Mutu, but the others didn’t live by the tikanga and kawa (rules and customs) of hapū and iwi, and talking wasn’t getting them anywhere.

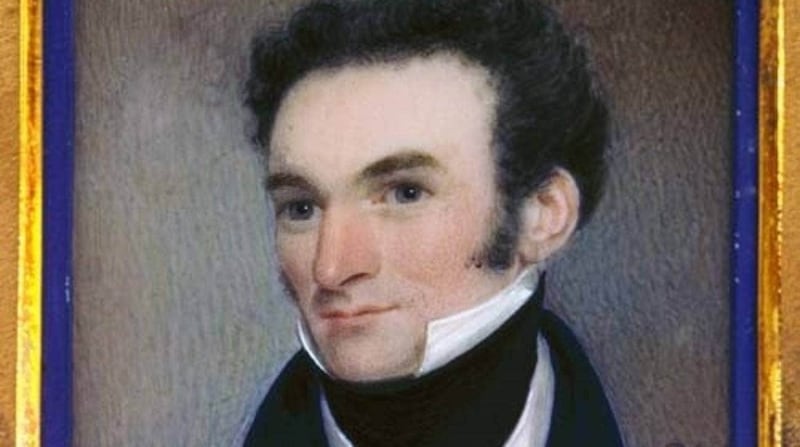

Enter James Busby, the King’s British Resident in Waitangi. He suggested a document inspired by the foreigners’ homeland might make a difference, planting the seed for what became He Whakaputanga o te Rangatiratanga o Nu Tirene, The Declaration of Independence of the United Tribes of New Zealand.

Of course, there were other reasons for creating the document, too.

According to Waikato University’s Professor Tom Roa (Ngāti Maniapoto, Waikato), iwi needed to protect themselves and their ships when embarking on trade voyages to other nations, and to retain the tino rangatiratanga of hapū from others, like the French, looking to plant their flag and claim parts of Aotearoa for themselves.

But for Mutu’s tīpuna (ancestors), Te Morenga of Ngāti Kahu and Te Rarawa, and Mātenga Paerata of Ngāti Kahu, Te Patukōraha and Te Paatu, signing He Whakaputanga, alongside some 50 rangatira who took on the group name Te Whakaminenga on October 28, 1835, was the answer to their problems with the Pākehā.

“It’s a statement of where sovereignty lies in the country, where control and authority lies, and it lies quite specifically with the hapū and their rangatira,” Mutu says.

“It was a statement of the obvious, but it was a statement that needed to be made quite clear.”

Mutu has translated the reo Māori version of the declaration and summarised it from the viewpoint of her tīpuna at the time.

Essentially, these are the four clauses of the declaration:

- That ultimate power and authority over the land lies with the hapū of Te Whakaminenga and an acknowledgement of this confederation of rangatira

- That the hapū and their rangatira of Te Whakaminenga are sovereign and will never cede law-making power over their lands

- Meetings will happen annually to discuss issues such as trade, where southern rangatira are welcome to join Te Whakaminenga

- And an English version would be sent to the King of England – who had already acknowledged the Flag of the United Tribes – with a request to aid hapū and iwi with the care and protection they give to the Crown’s subjects, with the addition of an ambassador to help stop any push to diminish authority of rangatira over their land and peoples.

Pretty clean cut, really. And King William IV must have agreed because he and the British government recognised it soon afterwards.

In a letter to Busby from Lord Glenelg, the Secretary of State for War and Colonies for the Crown at the time: “... His Majesty will continue to be the parent of their infant State, and its Protector from all attempts on its independence.”

But, as the past 188 years have taught us, that isn’t what really ended up happening.

Five years after the declaration was signed, another document, Te Tiriti o Waitangi, was crafted.

Mutu says that – at least for her tīpuna – part of it was that they were tired of trying to control the “lawless” ones traipsing about Papatūānuku, plundering Tāne Mahuta, and sailing across Tangaroa with little to no regard to their ture.

“Te Tiriti was an addendum to [He Whakaputanga],” Mutu says.

“It was just an add-on, saying, and this is how we will deal with Pākehā coming into the country, that we will allow them to come in, but they must abide by the law, and the person who is going to make them do that is the Queen of England.

“What was stated in He Whakaputanga about the mana and the rangatiratanga staying with hapū, that was just reiterated.”

Te Whakaminenga is even mentioned in Te Tiriti in clause one as follows:

“Ko ngā Rangatira o te whakaminenga me ngā Rangatira katoa hoki ki hai i uri ki taua whakaminenga ka tuku rawa atu ki te Kuini o Ingarani ake tonu atu - te Kawanatanga katoa o ō rātou whenua.”

It’s this clause that has sparked all the arguments.

What is kawanatanga? Te Aka Māori Dictionary says it means government, dominion, rule, authority, governorship, province – and it does now.

But back then, Mutu says, it was something very different, and you must read it from the understanding of rangatira at that time.

“That word is a borrowing,” she says.

“The translation you get these days would not work in there.

“We thought kawanatanga meant the Queen’s ability to keep her own Pākehā subjects lawful.”

From the other side of the pond, it meant all the rangatira gave up their authority to the Queen, as seen in the English version of the Treaty.

“The Chiefs of the Confederation of the United Tribes of New Zealand and the separate and independent Chiefs who have not become members of the Confederation cede to Her Majesty the Queen of England absolutely and without reservation all the rights and powers of Sovereignty which the said Confederation of Individual Chiefs respectively exercise or possess, or may be supposed to exercise or to possess over their respective Territories as the sole sovereigns thereof,” it reads.

Now, why would Te Whakaminenga, who just five years earlier declared to the Queen’s uncle, their independence, agree to the exact opposite?

They didn’t, Mutu says.

“The claim that we ceded sovereignty in Te Tiriti was a barefaced lie.

“There was certainly no discussion about the fact that the Queen of England was going to come in and take over the whole country. That did not happen.

“It set this country on the wrong path, and Māori have only ever tried to pull it back to what it should be.”

Flash forward 188 years, the New Zealand of today is very different to the Aotearoa envisioned by Mutu’s tīpuna.

If He Whakaputanga and Te Tiriti had been honoured, everyone would speak te reo Māori and English, and the language that is used to describe Māori, hapū and iwi would be worlds apart, Mutu says.

“They pushed us out of the way, thought they knew what they were doing. They have proven that they do not know what they are doing.

“We have been forced to take a back seat – or even be on the side of the road – while this British sovereignty behemoth went down the road, and watched the huge damage that has been done to this country.

“That’s why we come back and say, ‘Our tūpuna knew what they were doing when they issued He Whakaputanga, and when they allowed Pākehā to come into this country under the conditions that we set out in Te Tiriti’.”

He Whakaputanga and Te Tiriti laid the foundations for the growth of Aotearoa in the new world, but the world that stood on this whenua did not die out upon their signing, Mutu says.

“No matter what Pākehā do in this country, we are still mana whenua, and as mana whenua we will exercise our power and authority that we derive from the Gods, because we have no choice. We inherited it through our whakapapa and we have a responsibility.

“As much as they hate it, we are responsible for them and responsible for making sure that they live good, peaceful, fulfilling lives.

“You do not want your manuhiri left on the side of the road.”

Margaret Mutu is the Professor of Māori Studies at the University of Auckland, chairperson of Te Rūnanga-ā-Iwi o Ngāti Kahu and chairperson of the National Iwi Chairs Forum – Pou Tikanga.