A leading figure in brain injury research, Dr. Willie Stewart, has launched a scathing rebuke of a major study investigating head injury risks in rugby, suggesting that the findings may be compromised by conflicts of interest and lack of transparency.

Stewart, a consultant neuropathologist with a distinguished academic portfolio including honorary and adjunct professorships, questioned the recent findings from a collaboration between the New Zealand Rugby Union, Otago University and World Rugby in an interview with Whakaata Māori.

The criticised study - known as the ORCHID and championed by the NZRU - this week was promoted as providing a measure of head impact forces in community rugby, comparing them to everyday physical activities and claiming that the majority of these forces are less than or equal to general exercise impacts, like running.

However, Stewart’s pointed critique slams what he says are shortfalls in the research, directly challenging the study’s integrity, and saying a lack of a peer review undermines the whole thing:

“There is good reason why research is peer-reviewed before communicated. While far from perfect, the peer review system is designed to ensure that the questions addressed are appropriate, the methods employed are robust and the results are discussed in a dispassionate and balanced way,” Stewart elucidates.

The Glasgow-based neuropathologist’s concerns extend to the methodologies and communications surrounding the research. His first target? A potential for bias in the data representation, “We might debate some of the methods used here, in particular the choice of thresholding which gives an artificially optimistic view of head acceleration events.”

The study breaks down the impact of the individual hits into G forces, claiming 86 percent of knocks are about the same as a run, but the NZRU doesn’t spend much time on the cumulative effects of repeated knocks, especially the overall likelihood of concussive and sub-concussive hits during a player’s career.

A lawyer for a former New Zealand international pursuing the sport’s governing body likened prolonged on-field concussion impacts to cracking an egg.

“You crack an egg, right? Firstly, you only need to crack it once and you’ve got a mess... But, crack it again, and you’ve got one f****** hell of a mess,” he said.

“Get it? This is bull****.”

Stewart goes on to assert that the study’s independence is questionable, as it was funded by World Rugby and involved several of its direct employees, a detail disclosed in the manuscript’s footnotes but contrary to the media release claims.

He underscores the severity stating, “This then raises questions as to why a global sporting organisation would make claims of independence of research works, which they clearly are not,” an exasperated Stewart says.

Dr. Stewart’s criticisms come amid mounting legal pressures surrounding brain injuries in contact sports.

More than 400 rugby and football players, including former All Black Carl Hayman, who at 43 disclosed his battle with early-onset dementia, are suing the governing bodies of their sports as a result of health conditions in the years following their playing careers.

To add to the pile-on, Wednesday evening, the Royal College of Pathologists of Australasia (RCPA) confirmed a causal link between repeated head injuries and chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), a brain condition leading to cognitive, mood and motor disorders, now seen in individuals as young as 20.

The RCPA is calling on governing bodies to take action on CTE through five action points, which include a recommendation that low or no-contact versions of sports are played by rangatahi under the age of 14.

A litany of sportspeople across all fields of contact sports have been diagnosed with CTE in recent years, including former NFL linebacker Junior Seau, Chris Benoit, a professional wrestler, and Dave Duerson, a former NFL defensive back.

According to a study published in the Journal of Neurosurgery, an estimated one in five (19%) of people with CTE have died by suicide, including all three of the aforementioned.

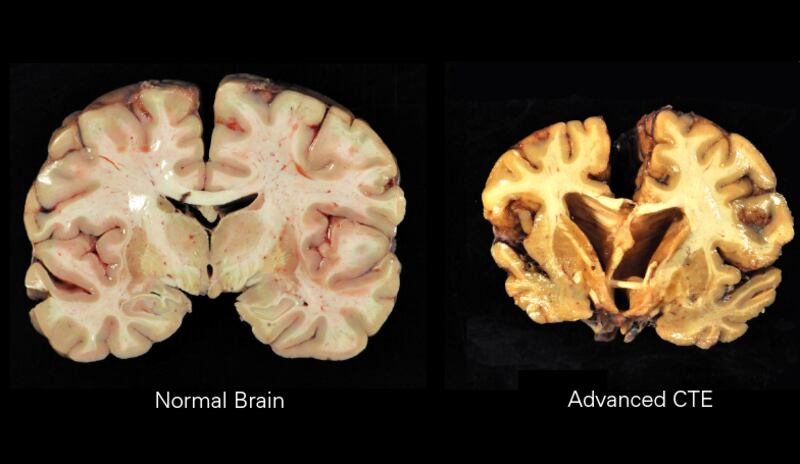

Until recently, it was difficult to diagnose CTE because there was no definitive test and it could only be diagnosed post-mortem. When examined, the brains of people with CTE show abnormal protein deposits and atrophy, the patients’ brains even weigh less.

Following the suicide of former AFL player Shane Tuck in 2020, an Australian university professor Dr Michael Buckland conducted an examination of his brain and uncovered the most severe case of CTE he had ever encountered.

Renee Tuck, the AFL star’s sister, said her 38-year-old brother’s injuries had developed so heavily, it caused him to constantly hear voices, making every day a ‘living hell’.

“Shane was the biggest, strongest, mentally strong bloke that I’ve ever known, and he ended up killing himself because his brain was just toasted,” she said. “I don’t want anyone to ever have to go through that.”

A revelation in 2020 indicated that ACC had incurred costs of close to $100 million for the treatment of sports-related concussion injuries in Aotearoa over the past five years. Rugby was by far the biggest contributor.

New Zealand Rugby said in its research statement it has an ‘absolute commitment’ to making the game as safe as possible and ‘reducing the risk of injury to our participants at all levels’.

It said the brain injury research came in the wake of other recent World Rugby commissioned research which claimed that playing rugby provided $1.5bn U.S. in preventative healthcare savings around the world, 30 per cent reductions in levels of childhood obesity, 15% reduction in heart disease and 33 per cent reduction in mental illness amongst adults.

Stewart says there’s an urgent need for unbiased and scientifically rigorous research to protect athletes’ health, slamming the joint NZRU and World Rugby press release he suggests was parroted by media.

“Beyond this glaringly inappropriate claim of independence, the focus of the release presents, in essence, a positive spin on head acceleration forces in rugby.”

He raged over the report’s claim that head injuries in the sport are somehow the responsibility of bad technique by players.

“The paper includes no studies comparing rugby head acceleration events to those of running, skipping or roller coasters [despite saying they were just as bad for brain health], nor are any data provided to support the claim that the higher force acceleration events are due to bad technique.”

He reiterated his view the integrity of research in the area remains crucial for the future of the sport and the safety of its players.

NZ Rugby provided the following response to Dr. Willie Stewart’s claims:

“Player welfare is a major priority for NZR and it’s important to take an evidence-based approach,” a spokesperson stated.

“We are actively contributing to scientific research which progresses the understanding of player safety in rugby, including head impacts.”

They emphasized the involvement of NZR personnel in “world-leading research” and maintained that “scientific integrity is always their priority.”

Addressing the scrutiny of the research, they affirmed, “These two particular research papers have both been peer-reviewed and published in reputable academic journals.”

They concluded, “There is significant work happening at all levels of the game to continue to make it safer and we welcome contributions to this, as well as productive, robust discussion.”