OPINION

MAMMA MIA!…security was tight.

Sweden is a country on a high terrorism alert. In fact, as the four-day conference concluded, some delegates were messaging from outside the Gothenburg Airport while a bomb squad scoured inside. Thankfully, it didn’t transpire to anything.

Given the 13th Global Investigative Journalists Conference (GIJC) was, apparently, the biggest-ever gathering of watchdog journalists, podcast producers and documentary directors on record, bag checks were compulsory outside the venue.

The reality is that for some delegates, their day job places them in quite dangerous situations. Tracking drug cartels, mafia and neo-Nazis across borders; investigating corporations, authoritarian rulers and political corruption; uncovering those responsible for massacres, war crimes, environmental carnage, human rights violations, abuse of power, disinformation campaigns; exposing the ongoing and often systemic violence against Indigenous peoples - not a profession for the faint-hearted. Not hard to get offside, either.

The Committee to Protect Journalists wrote in September that more journalists are killed each year uncovering corruption and politics, as are covering wars. That was before the most recent violent escalation in the Palestinian-occupied territories. As of December 8, the committee had recorded 63 reported deaths (the most since counting first began), three missing and 19 arrested by Israel.

As the sole participant from Aotearoa New Zealand, I was invited to join 2,137 reporters and editors from 132 countries in Gothenburg. Imposter syndrome is a thing. And I was soaking in it.

Offered a fellowship from the Indigenous Journalists Association (IJA) by Associate Director Francine Compton (Sandy Bay Ojibway), I came clean. Made sense…her being an investigative type and me barely having come to terms with being described as a journalist.

I’m the host, a reporter and associate producer of Te Ao with Moana (TAWM), the weekly current affairs series on Whakaata Māori. My son Hikurangi Kimiora Jackson is our producer. We’ve just wrapped on our fourth full season and were finalists at the NZTV Awards this month. I’m also a trustee and writer for the online Māori and Pasifika platform E-Tangata led by seasoned journalists Tapu Misa and Gary Wilson.

As for the ‘investigative’ bit? That’s more relevant to Cameron Bennett, one of our TAWM producers. Then there’s Paula Penfold, Toby Longbottom and the rest of the award-winning team at Stuff Circuit. I recalled that time long ago when the legendary Pat Booth delivered a guest lecture to a star-struck group of Auckland University first-year law students, including myself.

In August, I reached out to Nicky Hager who had attended the GIJC a few times. A recipient of an ONZM in this year’s King’s Birthday Honours, Hager was the first NZ journalist to receive a citation that specifically referenced his investigative work. He urged me to go, introduced me to his mates by email beforehand and provided sage advice.

“It is huge. Don’t try to go to every workshop,” he said. “Talk to people over a coffee or wine. Make a couple of new friends and it will be worth it.”

Whakaata Māori and Compton gave me a nudge. I got over myself. So glad I did. The whole thing was mind-blowing, from the opening address to our final “debriefing” in a Gothenburg bar…or three.

In my defence, we did need a blowout. I can’t say I came away from any workshop feeling particularly perky. In fact, it was kind of depressing. Well, apart from those sessions featuring our IJA crew where everything felt as familiar as a soft, warm blanket. It really is about whānau.

Compton asked me to chair a panel which featured Tuhi Martukaw (Pinuyumayan) from Taiwan, Brittany Guyot (Denesuline) from APTN Investigates in Canada and Tristan Ahtone (Kiowa) - an editor-at-large at Grist.

Ahtone described a two-year investigation called Land Grab Universities. He and Robert Lee (a history lecturer) revealed the extent, scale and impact of land taken illegally, and often violently, from Native communities on which some of America’s most prestigious universities have been built - “a massive wealth transfer masquerading as a donation,” wrote Ahtone.

The Morrill Act was passed by President Abraham Lincoln and turned “land expropriated from tribal nations into seed money for higher education…nearly 11 million acres.”

Some universities acknowledge they are beneficiaries of that dispossession. Even today, Indigenous people are pretty much conspicuous by their absence. While there are very few Indigenous governors, educators, students and mentions across the curriculum, on Morrill Act lands, there stand “churches, schools, bars, baseball diamonds, parking lots, hiking trails, billboards, restaurants, vineyards…”

Nice wee revenue earner if you can get it. Tax-free too.

That’s colonisation for you

Despite coming from Hawaii, US, Canada, Taiwan, Nepal, Sámi, Colombia and Aotearoa, our small cohort of Indigenous journalists discovered much in common.

Brittany Guyot described how her investigation for APTN Canada revealed the names of around 100 alleged abusers in Manitoba residential schools. Nuns and priests from two Catholic orders ran institutions purposefully designed to assimilate Inuit, Métis and First Nations children. Lawsuits filed in the late 1990s and early 2000s were dropped when the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement was finalised.

The abusers were rarely punished while the intergenerational trauma was clearly visible during Guyot’s interviews with survivors - echoes of New Zealand’s ill-named State Care system currently the subject of a Royal Commission of Inquiry.

Dev Kumar Sunuwar, a co-founder of Indigenous Television in Nepal, described the pressure and dangers placed on Indigenous peoples in the face of a state determined to build hydro-power plants on native lands. Tuhi Martukaw shared similar stories she had witnessed in the Philippines.

We also explored the struggle to attract interest in Indigenous stories inside mainstream newsrooms; the push to grow numbers and capability of Indigenous reporters; one-dimensional misrepresentation and sheer invisibility of diverse native voices; the under-resourcing of independent Indigenous newsrooms; as well as a lack of time and mentoring to develop investigative skills.

I mentioned how NZ media company Stuff, following the lead of National Geographic and others, ran an audit of its own portrayal and representation of Māori across 160 years. Admitting itself to be racist and blinkered, Stuff issued an apology to Māori.

I also reflected on the Public Interest Journalism Fund, a strategy to support roles, projects and industry development throughout the Covid-19 downturn. That fund helped stimulate a more diverse cohort into our newsrooms while nudging platforms into considering actions to bring Te Tiriti to life. Watching these fresh young Te Rito cadets being mentored by Whakaata Māori, Newshub and NZME teams was exciting. Watching the upturn in regional reporting was just as exciting.

On November 27, the day he was sworn in as New Zealand’s new Deputy Prime Minister, Winston Peters suggested the $55m fund was ‘bribery’ to ‘state-funded media.’

A week later, the New Zealand First leader spent most of his parliamentary speaking time lambasting the media.

In Sweden, Vanessa Teteye Mendoza told us that simply being a journalist in Colombia was dangerous, and how she built and supported community initiatives through her independent intercultural media agency Agenda Propia to give a voice to Indigenous communities of the Amazon.

Into the light

The Global Investigative Journalists Conference was all about shining a light on truth. And believe you me, there was a lot of darkness in many presentations. Digital mercenaries, cyber threats, digital warfare, A.I. – these were recurring themes in the half a dozen workshops I attended.

“I’m really worried about where we sit right now,” admitted Citizen Lab Director Ron Diebert. “The ‘new normal’ is mercenary surveillance firms that are almost entirely unregulated selling to the world’s worst sociopaths.”

Diebert delivered the opening keynote at the conference. He described digital espionage as an epidemic that required journalists ‘go on the offensive’ and explained how a number of democratic governments are also ‘enthusiastic clients’ of these spy firms.

Given the GIJC was big on practical stuff, delegates were able to grab a coffee in the foyer while their phones were checked for spyware.

Guardian and Observer reporter Carole Cadwalladr is famous for exposing the Cambridge Analytica scandal that revealed a misuse of data from Facebook for political gain. The firm was involved in Trump’s campaign as well as Brexit. The theme of the panel was influencing elections. Given New Zealand was only around three weeks out from ours, I was all ears. I had flashbacks to the gripping content and impact of Hager’s Dirty Politics as I took my seat.

“In the next 18 months,” Cadwalladr stated, “Half of the world is going to the polls…and at the same time, we have these incredibly powerful new tools being unleashed.”

Cadwalladr warned that because elections are a ‘singular event,’ they are a ‘zero-sum game that attracts motivated actors and lots of money.’ While money spent in the digital space can’t easily be tracked, her panel suggested it was important to look at companies who might benefit from an election campaign and to search for advertisements they might be placing on social media platforms.

The first question from the floor was more of a statement. The reporter declared he was ‘unconvinced’ by Cadwalladr’s work. Cue sharp intake of breath from the rest of us.

“I focused on whether the conduct was legal,” replied an unfazed Cadwalladr. “And it turned out not to be, so…”

The panel also explained how companies such as X/Twitter and Facebook ditched filters applied during past elections, allowing propaganda and misinformation to seep through. So much so, that even when authoritarians like Trump and Bolsonaro lose an election, they still win. I thought of home and how words like ‘freedom and democracy’ have become red flags for something else - and how terms like ‘apartheid’ had been distorted.

I quite like a challenge. It’s probably why I got into journalism. Put the facts out there, unpack the layers of complex issues, help people connect the dots and boom - everyone will get the picture. It was pleasing to note I was not the only optimist in the room.

“What advice can you give us?” asked another from the floor.

Great question, I thought.

“Pray,” was the sobering response.

Jesus.

The panel reminded reporters that evidence-based journalism doesn’t really cut it with those who have fallen victim to ‘half-truths’ peddled by ‘multiple parties across multiple platforms.’ Covid hammered that one home back in Aotearoa. After the session, I introduced myself to Cadwalladr as a ‘fan girl from New Zealand.”

“New Zealand?” she said, eyes widening with interest. “One of my ‘Brexit boys’ has been down your way.”

Arron Banks bankrolled the Leave.EU campaign and is believed to have made the largest individual donation in British history to any political campaign. While based in NZ in 2020, Banks was quite taken by a certain politician who campaigned against the ‘woke’ during that election.

“Winston Peters,” she recalled.

“He’s probably going to get back in next month,” I replied.

No need to be a flash award-winning investigative journalist to pick that one…

Tracking Political Extremism

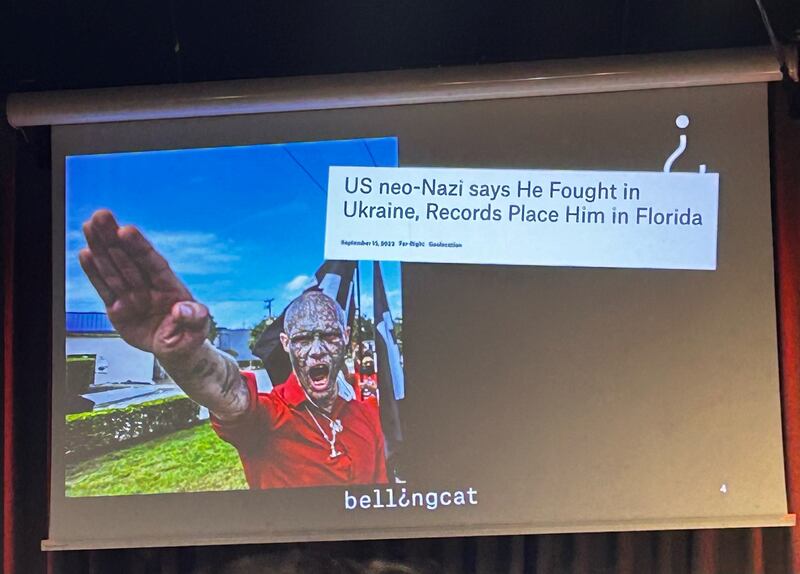

Michael Colborne from Bellingcat Monitoring described how most far-right extremists leave a digital footprint which often catches them out. Colborne explained how he had tracked American neo-Nazi influencer Robert Rundo across Eastern Europe. A violent offender with a penchant for fight clubs (and his own far-right fashion line), Rundo is now in US custody after having been extradited from Romania.

The journalist explained how three months after his story on Rundo was published, the fugitive was booted out of Serbia and disappeared. Scouring other social media platforms to figure out where Rundo’s mates were, the Bellingcat team settled on Bulgaria.

In March, and with a new tracksuit line to flog, the extremist uploaded a selfie onto Telegram. He blurred the background. All that was visible were a couple of yellow-striped bollards on a cobbled street and a stop sign on the corner behind him. Having visited Bulgaria, Colborne knew neither Sofia nor Belgrade had yellow bollards.

(I mean…who notices stuff like that?)

Using Google Lens and Google Image Search, it took Colborne ten minutes to figure out exactly which corner of what street in which town (Stara Zagora) the violent extremist was in.

I was impressed. But the thing is, not all white nationalists wear tracksuits and get arrested in gyms. Some scrub up in tuxedos.

Hannah Gais from the Southern Poverty Law Centre was on the same panel. She and a colleague infiltrated a Republican fundraising gala in New York, after a heads up that a bunch of radical extremists would attend.

During the night, the duo took selfies and photographs of each other to capture images of polarising figures in the background. They heard Majorie Taylor Greene declare from the stage that if she and Steve Bannon had planned the 2021 attack on the US Capitol, ‘we would have won’ and those responsible would have been ‘armed.’ The article is worth reading.

Another memorable session featured award-winning journalist Valeriya Yegoshyna. While she previously focused on corruption and misuse of power in the Ukraine, after the Russian invasion Yegoshyna switched to investigating alleged war crimes.

After over 400 bodies were found buried in the forest, Yegoshyna and her project editor Kira Tolstyakova went to Izyum where they embarked on a mission to identify Russian military and special service agents responsible. They worked alongside local volunteers or “diggers”: people who had photographed and then buried the bodies of the dead. The pair combed documents and even records of phone calls intercepted by Ukraine Secret Services to identify the Russian commander who had ordered the atrocities.

Proof again that everyone has a digital footprint, one that can trip perpetrators up. The investigation by Schemes/Radio Liberty is an incredibly grim read.

Equally grim is the Bandit Warlords of Zamfara, a BBC Africa Eye documentary which won a Shining Light Award at the conference. BBC journalists had heard of a military strike in the north of Nigeria targeting armed groups. They also knew there were few trained journalists on the ground.

BBC Executive Producer Daniel Adamson noticed a young law student on Twitter. Noting he wasn’t far from the action, Adamson reached out. Yusuf Anka was eventually recruited, given an iPhone, tripod and audio recording equipment, as well as mentoring in editorial direction and technique. From a distance, the BBC team mapped his every move and wrapped security protocols around him. Each day, Anka would mount his motorbike with his kit of equipment and ride for hours.

But then the story focus changed. Anka wanted to unpack the dynamics around why armed motorcycle gangs were terrorising locals; that was the real story in his mind. At great personal risk, Anka ended up interviewing bandits, warlords, community leaders and whānau of victims. After almost three years of filming, the BBC flew him to London where he and a team of editors finally completed the documentary for release.

The Nigerian Government wasn’t happy. It considered banning the BBC. The warlords weren’t exactly thrilled either. But the villagers felt seen and heard. It forced a difficult conversation in the country.

The point Adamson made to gathered journalists was the same shared on the Indigenous panel - those on the ground and connected to the community know best. Often ‘civilians’ not journalists can be the key to bringing light to truth. Trust in them, keep them safe, and stay in your lane.

Stuff it…

Every speaker was required to link their investigation to practical tools and tips.

Simple stuff. When it comes to investigating elections, reporters were urged to collaborate with colleagues from other media, even internationally, because some of the same tactics and political manipulations are at play across several countries.

Techy stuff. Ron Deibert recommended that investigative journalists with iPhones immediately enable Apple’s new “Lockdown Mode.” This helps protect devices against rare but sophisticated cyber-attacks. He suggested reporters seek forensic analysis if they receive notifications of suspected breaches from Apple.

Sensible stuff. When tracking extremists, Michael Colborne advised journalists to always use a VPN to hide their online footprint from those who might resort to intimidation.

Helpful stuff. There were toolkits on how to investigate whether governments are delivering on their commitments around the climate crisis and digital threats.

There was much practical advice around safety, data collection and mapping tips; use of satellites and apps; notes on how to read files, recognise money laundering, green and ‘native’ washing; how to combat disinformation and trolling, and information on the verification tools. Some of it was too technical for me. Ahtone too. During his Land Grab universities investigation, he hired a couple of people to create new ways of capturing and displaying data. Win-win.

Food for thought…

In between sessions, I’d tuck into the healthy little lunch boxes and chat with others, like the Associated Press reporter focused entirely on the climate crisis, another from Le Monde monitoring corporate lobbying and toxic industries; and others looking at the global influence of tobacco and oil companies.

At the end of each day, I’d wander Gothenburg with my new whānau. One night we went in search of ‘Swedish meatballs.’ Our crack investigative team surmised they were probably just called ‘meatballs’ in Sweden.

The most sustainable city in the world was nerve-wracking for visitors trying to avoid being taken out by a cycle, scooter, bus or tram. Not easy with massive jet lag…or after a couple of wines.

Heads up. Gothenburg is also a cashless city. It doesn’t pay to lose your phone or cards. Big shout out to Lost & Found at the huge Dubai International Terminal. The guys next to me were equally thrilled to be reunited with their lost passports.

The conference was like being immersed in a series of dramatic thrillers. Investigations that have taken years condensed into 20-minute presentations. It gave me pause to reflect.

Given how dangerous some countries are for journalists, activists and Indigenous people, I felt blessed to live at the bottom of the South Pacific. But worried, as well. Talk of ‘media bribery’ by a senior politician is fuel for those pushing disinformation campaigns on unregulated platforms. Those ‘multiple players across multiple platforms’ - think tanks, white supremacists, corporate lobbyists, cartels and catastrophists - they’re among us.

Then again, as a small country where language is not an issue, we are more agile than many overseas. We can mobilise quickly. We also have Te Tiriti o Waitangi and He Whakaputanga o te Rangatiratanga o Nu Tireni, even if a bunch of people would rather magic them both away. NZ is a very secular society and there is still freedom of the press. Media platforms have yet to cave in completely to the drive for churning out quick-fire stories to attract advertisers and ‘consumers.’ Longform, quality journalism is still valued.

The conference was an opportunity to plot, learn and collaborate. And demystify the word ‘investigative.’ It turns out that investigative journalism is really the kind of journalism most of us do, but with the luxury of much more time to do it in.

I was probably the only one walking around with ‘Mamma Mia’ playing high-rotate in my head. Well, apart from Brian Pollard (Cherokee) of Associated Press - both of us lucked out finding ABBA tees. But what I took away from the 13th Global Investigative Journalists Conference haunts me long after those peachy-keen lyrics faded.

I’m hoping to organise a group to attend the Indigenous Journalists Conference in Oklahoma City next July. As the US heads into its elections, the role of Indigenous and investigative journalists will become even more vital. Meanwhile, I’m listening to the fascinating podcast investigation The Empty Grave of Comrade Bishop by Martine Powers, through the Washington Post.

Applications are now open from countries keen to host the 14th GIJC for 2025. They’re looking for a country that values journalism; is warm and safe and beautiful.

Just saying…

Te Ao with Moana screens every Monday 8pm on Whakaata Māori/Māori Television. All episodes are available On Demand. The series will return in March 2024.