For hundreds of years, tattoos in Japan have famously been associated with gangsters, the Yakuza.

Despite the prevalence of tattoos in modern culture the stigma appears to still exist.

That’s been an issue for Māori, with tā moko, mataora and moko kauae, when they travel there. But are attitudes changing?

Te Ao with Moana reporter Jessica Tyson went to Japan to find out.

Tatsuya Mizuno is a journalist who specialises in crime reporting. He says the reason tattoos are taboo is because they’re associated to Yakuza, a Japanese gang that covers their entire body with tattoos.

“They’re probably the oldest crime organisation. They’ve been around for 400 years or something. So, those guys have got tattoos everywhere…And even my generation, I was born in 1959, having tattoos is like, ‘oh, no, no, no’.”

Tattoos in Japan are not illegal. But traditionally, attitudes are more conservative, and while some view tattoos as an art form, the Japanese government, on the other hand, does not.

During his career, Mizuno has seen tattoos go from being exclusively gangster to becoming more accepted.

“Things started to change probably back in the nineties.

“Young generations started not to care and just started having tattoos. So probably, people over 50 are negative about tattoos, but probably people under 50, 40 have no problem with it.”

Tattoos have long been banned in public onsen, hot springs, and bathhouses, but in the bigger cities, exceptions are being made.

“In big cities, if you go to public bath houses it used to be, ‘Hey, you cannot get in’. But now I think most of the public bathhouses in Tokyo, Saka in big cities, yes you are allowed to get in there. And hot springs as well,” says Mizuno.

“If you go to the countryside, probably people’s attitude would be a bit different.”

Also contributing to the change in attitudes could be because the numbers of yakuza are also decreasing, says Mizuno.

“I think they have been sort of losing power for the last 20 years and there used to be more than 200,000 all over Japan. But now, police have started to crack down hard. So I think now there are less than 50,000. So they’re kind of dying.”

History

According to The Japan Times, the Japanese tattoo culture dates back to the Jōmon Period (10,500 to 300 BC), “when clay figurines were molded with marks that modern historians interpret as either tattoos or scarification.”

During those years it was common for Japanese to use tattoos as a form of punishment, reserved for those who committed the worst of crimes.

The 17th century marked the end of tattooing as a punishment, but it was the start of a ban on them entirely.

The Japanese government saw decorative tattooing as a way for criminals to cover up the ink they received as punishment.

The yakuza favoured tattoos, and getting one showed signs of courage and loyalty to the gang.

In 1936 after war broke out between Japan and China, tattoos were banned entirely because the government thought people with tattoos were problematic.

It wasn’t until 1946 that tattooing became legal again.

Responding to an inquiry by the National Police Agency, the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) declared that “coloring skin by injecting colors into it with a needle” is a medical act. It meant anyone who participated in the act of tattooing without a medical license violated the Medical Practitioner’s Act.

As recently as 2019, during the Rugby World Cup, the All Blacks were going to great lengths to cover their moko so as not to offend Japanese attitudes. Tattoos were officially taboo then, but now, people like Mizuno are recognizing moko for what it is.

“It’s definitely an art. That’s all I could say. It’s beautiful. Those guys who have tattoos on their face it’s fantastic.”

Moko in Japan

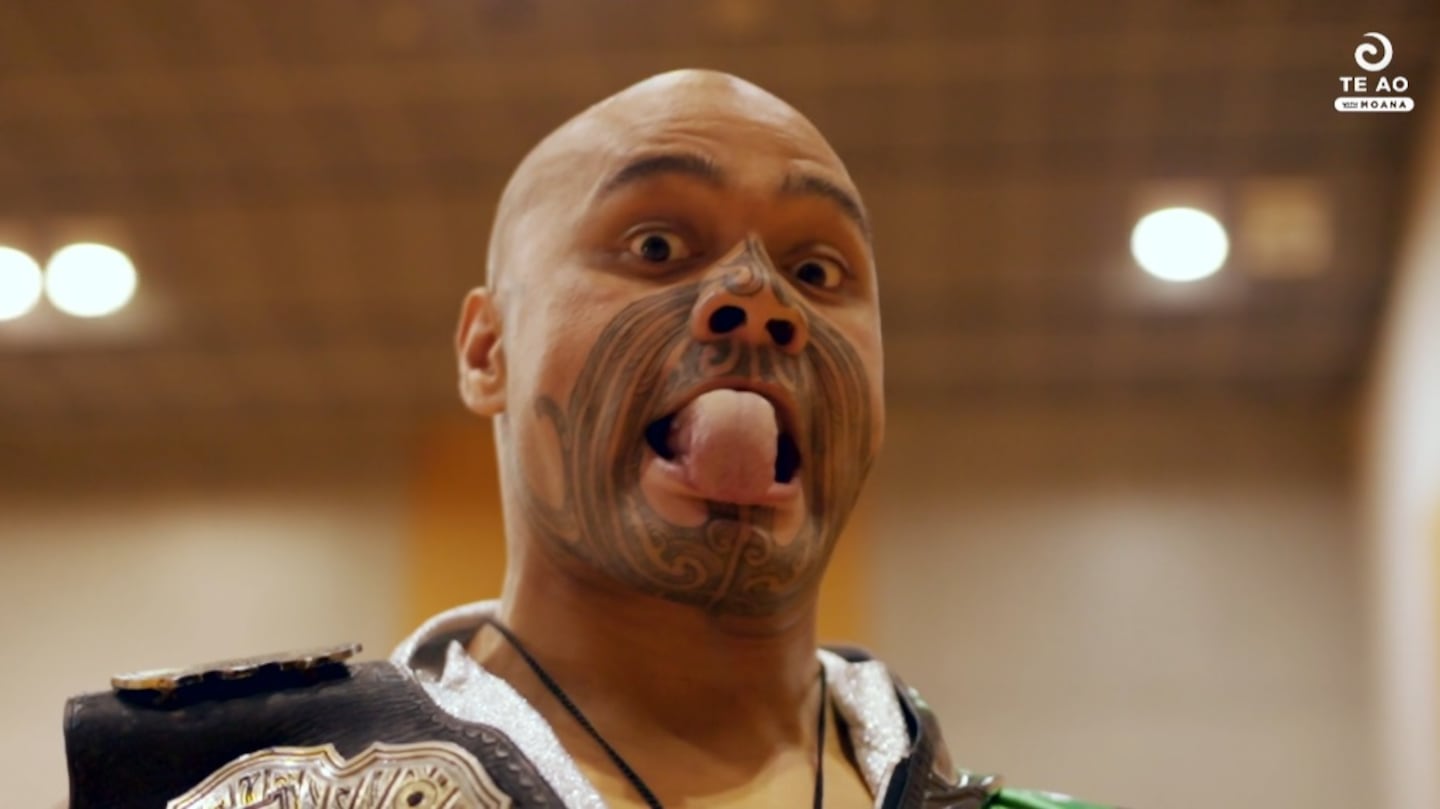

Aaron Henare, of Ngāpuhi, Ngāi Takoto, Te Arawa and Ngāti Kuri, is a professional wrestler signed to New Japan Pro-Wrestling under the ring name Henare.

He’s been living in Japan for eight years and wears his mataora proudly. He says the reaction to the taonga has been nothing but positive.

“There’s been no problems on the street. There’s been no problems going anywhere. In the gym, I wear a mask because I respect their tikanga. I don’t wanna scare anyone if [I’m] pumping weights in the gym. As long as it’s respectful they’re all right and the fans love it. They’re like, ’Wow, I can’t believe he loves his people so much that he is willing to do that.’ It’s like a different level of respect they have.”

Tikanga in Japan

Henare says he doesn’t believe he is breaking Japanese tikanga with Māori tikanga by wearing mataora.

“I don’t think it’s mutually exclusive. There’s no tikanga that does cross over like that does cancel one other out. I think we’re quite similar. You respect your family, you respect your elders. If your elders ask you to do something, you do that,” says Henare.

“In terms of the tattoo, maybe they feel offended, but they will never say, they’ll never offend your tikanga just to preference theirs which is a massive respectful thing that the Japanese people do. Because they’re so prideful of their culture, they will never, ever take away from another culture to do that. Especially if you’re a visitor, if you’re manuhiri in Japan, they’ll do all they can to respect you and make you feel welcomed.”

Henare returned home to Aotearoa last year to receive his mataora by kaitā Raniera McGrath, alongside his whānau. He says his mataora represents his whakapapa.

“Studying the whakapapa was the main reason that I got it and most of it represents the tūpuna obviously. Like when I discovered who I was, it just gave me a sense of empowerment, but also my accomplishments as well.”

Henare’s most recent accomplishment was becoming the first Māori to ever win one of the most prized belts of the New Japan Pro Wrestling (NPJW) organisation, a company that has previously had the likes of Hulk Hogan, Andre the Giant, and Muhammad Ali compete.

He won it just last month after defeating four-time belt winner Takagi Shingo to win the Never Openweight belt.

“[It] means you’re not a heavyweight, you’re not a cruiserweight, it’s open, it’s like absolute... It’s like one of the most hotly defended titles in the world,” says Henare.

Since having his mataora his managers at NPJW have also been supportive.

“It’s been pretty well covered... We’ve done articles and podcasts and interviews, explaining this is a part of our culture. This is one of our rituals. This is one of the things that differentiates us as Māori people,” says Henare.

“And then they’ve already known about the All Blacks from the World Cup a few years ago. So Māori culture has come to the forefront … It’s been quite positive actually.”

Horimasa Tosui is a master tattoo artist. He practices the traditional method, tebori, which dates back to the 17th century.

Tebori consists of using a hand poke, a wooden or metal stick with a set of needles fastened to the tip to insert ink into the skin. The technique provides a unique look to tattoos making them unusually vivid and life-like.

“タトゥーを彫ることがすごい大好きなんですよ楽しいんですよ彫ってる時間がすごい楽しくて - I love doing tattoos immensely. It gives me joy. I have an amazing time making them. I always do.”

Tosui agrees that attitudes are changing.

“もちろんありますそれはちょうど多分1980年代90年代とかになってきて海外のタトゥーが日本にも入ってくるようになったんですそういう雑誌だったり例えば そのう ミュージシャンやアーティストのがタトゥーを入れているとかそういう情報がやっぱり日本にも入ってきてそれがもう少し日本の伝統姿勢とかとまた違ってもう少しソフトに見えたし若者に入りやすかったんですね受け入れやすかったんで - It was probably around the 1980s or 1990s that foreign tattoos started coming to Japan. For example, through magazines. They would feature artists and musicians that were getting tattoos. That kind of information reached Japan. The tattoos looked a bit different from traditional Japanese-style ones. They were a bit softer and more accessible for young people.”

Tosui’s clients are anything but gangsters.

“普通の会社員とか一般の人でも入れてる人はいるしワンポイントタトゥーだったりアメリカンヨーロピアンスタイルの タトゥーだったらもちろん若い子も今いっぱい入れてるし - Many of my customers are corporate employees or regular people. Some people get small tattoos. Many youngsters these days get American-European style tattoos.”

Tosui’s profession as a tebori artist was once illegal in Japan. It’s not anymore but he still feels the need to keep it on the downlow. He’s been practicing the art for the past 28 years.

“プロの彫り師になってから3年後くらいに家族に告白したんですけども最初怒られるんですけども怒られるのかなと思ったんですけど意外と普通で頑張りなさいって言ってくれました応援してくれました - About three years ago, I confronted my family about becoming a professional tattoo artist. I was quite sure that they’d get angry in the beginning, but they were surprisingly supportive, and encouraged me.”

Another interesting aspect of Japanese tattooing is that a tattoo artist is required to be formally qualified as a medical doctor.

タトゥーが入ってない人一般の人から見たらやっぱりタトゥーってまだイメージが悪いものなんでどうしてもそれを彫る側となるともっと気を使わなければいけないというか. In the eyes of the common people who don’t have tattoos, tattoo doesn’t create a great impression. And being a tattoo artist, I have to be more cautious.”

But what comes as a big surprise is that Horimasa does support covering tattoos in public, but for different reasons.

“隠して損はないと思ってます はい特に日本の伝統姿勢でもちろんイメージとしてはすごい怖いもちろんイメージとしてはすごい怖いなんかポピュラーになりすぎるとなんかちょっと価値が落ちるというか怖い感じというか怪しい感じがそのタトゥーの日本の伝統姿勢の魅力でもあるし魔力でもあるようななんかそんな感じがします- I think nobody should hide it but it’s harmless even if you do. Especially the traditional Japanese approach portrays it as scary but really cool. I believe, if it becomes overly trendy, it will end up losing its charm. That seemingly scary or mysterious feel of it or a rather glamor and magic in terms of traditional Japanese approach will get lost.”

Tosui’s client, Ken, says for all their edginess, tattoos, he says, have also become a cultural expression.

“どんな思いで入れてるかっていうそのデザインと違った価値観やアイデンティティみたいのがあるなと思っているのでやっぱその点消えないデザインを体に刻むっていうのは非常に深い意味があることだなと思ってます個人的にそのう個人的にはあのう社会が入れ墨に対して日本国内が寛容にならなくてもいいなとすごい思ってましてやっぱ長年ついてきたイメージを払拭させるのってすごい難しいことなので - What matters is your thought behind your tattoo. It’s the uniqueness in the design which gives you a distinct sense of value and identity. Making a tattoo without losing that sense gives a deep meaning to it. Well, personally it’s okay if the society shows no tolerance for tattoos in Japan. Naturally, it’s quite a challenge to toss away the image associated with tattoos.”

Just as serious for Henare is his Māori identity. He wears his whakapapa with huge pride when he’s in the limelight as a pro wrestler.

“I could take this back home. I could show everybody, I could go to schools and be like, bro, this is possible. All I did was dream. You’re only as big as your dreams. So I’m just hoping some Māori kids back home see me and they’re like, ‘Wow, there’s a Māori wrestler. I’d love to do that too.”

Henare has returned to Aotearoa this month to compete at the Kiwi Rumble event at Pakūranga College in Tāmaki Makaurau this Saturday, July 13.