If the on-screen comments during last night’s Te Tiriti o Waitangi debate were anything to go by, viewers were captivated by Helmut Modlik.

The Ngāti Toa Rangatira chief executive was one side of the debate coin, up against Act’s David Seymour, the architect of the Treaty Principles Bill.

But who is he?

E-Tangata’s Dale Husband caught up with the Ngāti Toa leader in early September, before David Seymour accepted the invitation to last night’s debate.

This interview was originally published in E-Tangata and is republished here with permission.

Tēnā koe, Helmut. I always start with names because they can be very revealing. Can you tell us about yours? Because it’s a slightly unusual name for a Māori man.

I’ve made a habit over my life of telling people I’m just a Māori boy from Takapūwāhia with a flash name.

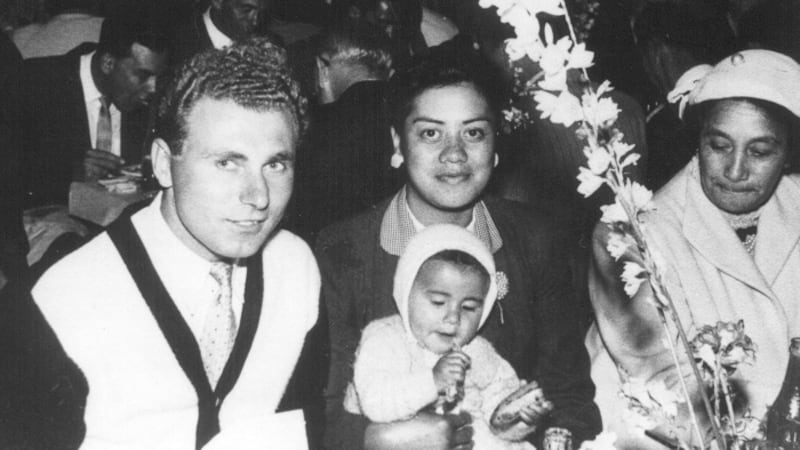

The back story on my blinking name is that a National government contracted an Austrian company in the 1950s to come out to Aotearoa to build state houses. They turned up here, these square heads, as my mother called them, 120 men on their motorbikes. They brought their own wood, they brought their plans, and three of them ended up marrying three Ngāti Toa cousins from Takapūwāhia. And my dad was one of them. That’s how come I’ve got a flash handle, bro.

Have you been to Austria to meet that side of your whānau?

I have. My dad went back to Germany in 1968, when I was about six, leaving my mum (Haneta Rebecca Arthur) with her five kids. I grew up in the pā, surrounded by my uncles and aunties, and, when I asked my mum where’d Dad gone, she’d say: “Oh, he’s joined the Luftwaffe.” You know, the sort of nonsense our people say — well, certainly, my gang does. So I never knew much about my dad’s people.

As I got older, I looked into it — and I did go over there and visit where he was from. It wasn’t easy to be there. It was interesting but very, very, very different from our people.

I guess with that name, you might’ve been subjected to some ribbing and the like.

I’ll tell you a quick story about that, bro. My mum’s one of 14 siblings, and her dad (Karewa William Arthur) was one of 15. So, when you’ve got a million kids running around the place, parents aren’t very patient with kids having a howl and saying so-and-so did this and that. And when I was a little boy, my mum said: “Son, if you come home crying to me because somebody’s given you what-ho, I’ll give you another crack. Take care of your own business.”

So when I turned up at primary school — true story — my first two weeks, every play time, every lunchtime, I was chasing boys who were getting smart to me about my name and having fights. It only took two weeks. But from that day to this, nobody’s ever given me nonsense about my name again. So that was the dynamic associated with my handle.

How does it work for your son?

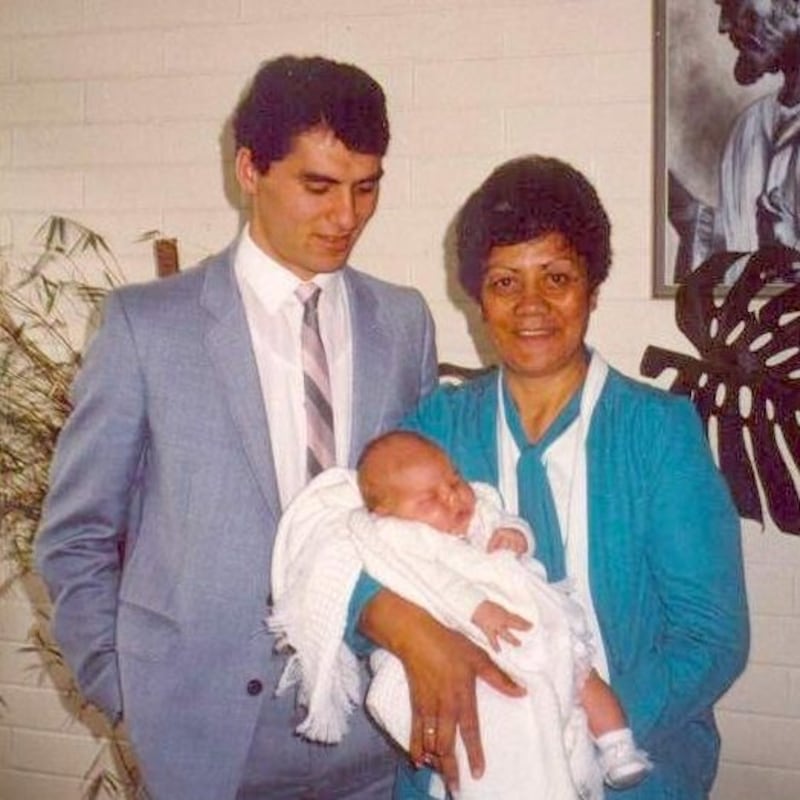

Well, different time, I suppose. The reflection on that is that when I got to be a father and my boy turns up, my firstborn, I talked to my wife about a name. I said I was inclined to give him my name, as an incentive to me to be a good father and be a man. So that one day, when my boy met people who’d known me, they’d give him a smile and shake his hand and show him an open door.

It’d be an incentive for me because it’s a name you can’t hide from. Well, that’s what I thought as a young man. It would be an incentive for me to make it a name that my boy won’t be embarrassed about. And that’s what I did. No doubt he got his fair share of ribbing about his funny name, but he’s turned out okay, so we’ll go with that.

Porirua’s home, but there’s this interesting connection to Taranaki as well, yes?

My nan, my mother’s mother, is Kauhoe Manuirirangi. The Manu whānau are from up Manaia way, in Taranaki, so I always wondered: “How the heck did my koro end up all the blinking way up in Manaia?” This is in the 1920s. I asked my mum one day, and she said: “He walked there.” Eh!?

He was looking for work, and he just kept on walking until he found work. There was no benefit in those days, of course. And life was a lot simpler but a lot harder too. My koro walked from Porirua to Manaia, where he found work on a farm. That’s where he met my grandmother. The Manu family up that way — they’re a big, big whānau. When they got married, they started life in Manaia, had their first few kids, and then ended up coming back down to Takapūwāhia here. My mum and her other siblings — at least the first four — were born up in Manaia. The rest were born down this way.

But our whānau up there, we’re very close, and over the years we would go back and forth. Obviously, Ngāti Toa and Taranaki have deep and enduring whakapapa links. There’s very few if any Ngāti Toa people who don’t whakapapa to Ngāti Tama, Te Ātiawa, and Mutunga. So that’s an easy and continuous source of hononga and aroha for us.

And it’s a beautiful place. I mean, even to this day I shake my head any time I go up there and have a look around. The only sadness is that it’s all emptied out. Everyone’s gone to the cities. But, yeah, soft spot in my heart for my nan’s people and all the whānau up there, for sure.

Your mum raised you mostly on her own. She must’ve been a neat wahine. What traits did she carry that you loved?

Ngāti Toa has always been over-endowed with wāhine toa, bro, and she’s one of them. In all seriousness, I can’t speak for any other iwi, but in our little iwi, we have very famous women all the way through, even in the days of our taniwha, when Te Rauparaha was doing his thing. All my life, I’ve been surrounded by strong women who make sure that everybody, men and children, are doing what they should.

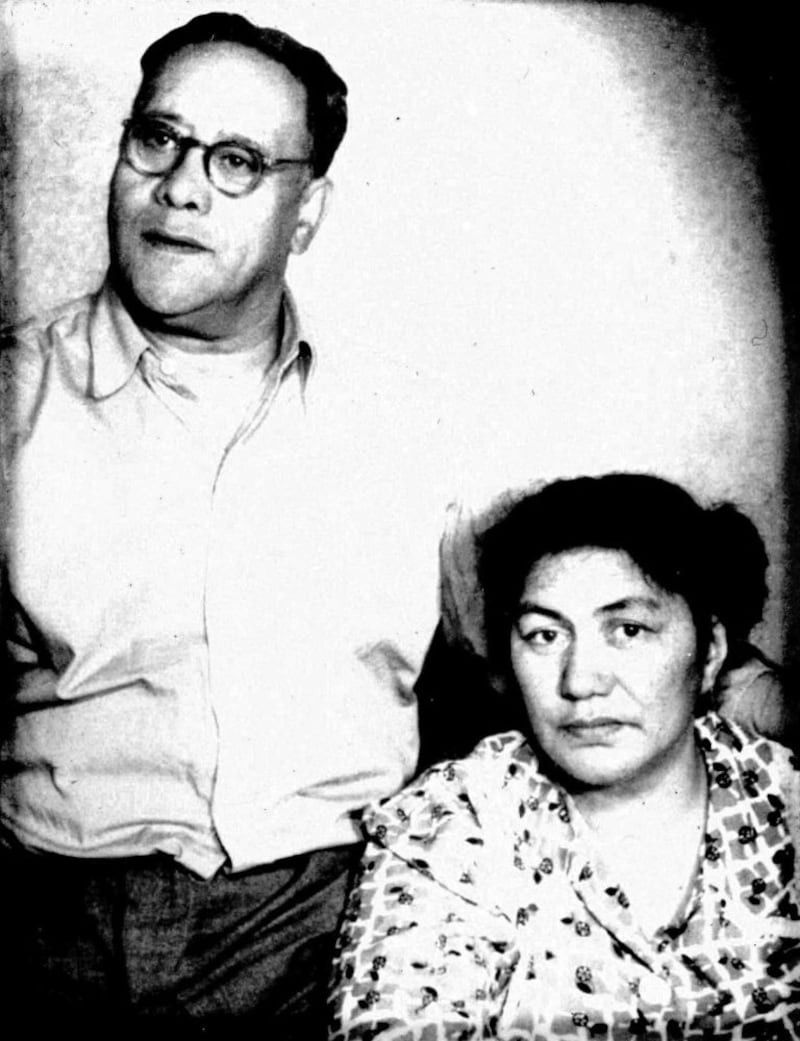

My mother was certainly no exception to that rule. She was one of the oldest in her family. There are 10 boys, four girls — but of those four girls, the oldest was whangai’d off, the youngest wasn’t born until my mum was older, and her little sister was given to her grandparents to raise. So it was really just my mum and her mother in this household full of men. It was a hard life. My mum used to say: “All of these useless men.”

And then she was a woman herself and raising her family as a solo mother. So yeah, my mum did it hard. She was loyal, hardworking, everything you’d want your mother to be.

I have a photo of my mum on my desk. I say hello and have a talk to my mum every day. I’m 62 years old. She’s been gone for 25 years.

If I’m anything, it’s because of her. Simple as that.

I’m a Watene, too, so I’m not unfamiliar with the LDS. You didn’t go to Church College, did you?

I did, bro. I’m a basketball player. You had to go there if you wanted to fulfil those aspirations.

You did your LDS mission in Aussie? Where did you go?

Melbourne. I’ll give you a bit of background. In the late 1800s, the Anglicans really dominated the Christian space, probably in most places in Aotearoa, certainly down this way. But there was a raru down this way between the Anglican church and Ngāti Toa in connection with Whitireia, our whenua here that was given to the Anglicans to build a school on. They didn’t do that, and then disposed of the land, and one of our rangatira, Wi Te Kākākura Parata, sought to get it back. That dispute ended up going all the way to the highest courts of the land, and ultimately resulted in the infamous decision by Justice Prendergast that the Treaty was a “simple nullity”.

That case involved Ngāti Toa, Whitireia whenua and the Anglican church. As a consequence, our people were a bit grumpy with the Anglicans. Not too many years after that, some American Mormon missionaries came around to see if anyone was interested and they got a hearing. That’s why the LDS faith ended up taking root and having quite a good reception amongst our community during the 20th century.

I grew up always going to church, doing what I was told. But you get to a stage in your life when you have to decide who you want to be. I was serious about my faith at that time, so that’s what led me to serve as a missionary. It was an extraordinary experience. I mean, you ask a 19- or 20-year-old to sell everything they’ve got, no longer play basketball or date girls or pursue their careers, and spend a couple of years serving strangers and being helpful and talking about things that have an intergenerational eternal perspective. That’s not an easy ask. For me, it was a transformative time.

And I mean, I don’t want to be rude to Aussies, bro, but they’re a godless bunch and it was hard yakka. I had to draw on all my reserves not to get in trouble, with some of the treatment I got over there. But I look back on it as being one of those crossroads moments in my life.

You studied to a high degree. I’m curious who might have been influential in that path.

I mentioned that my mum was a hard worker, and she was determined that her sons would not be useless like her brothers, at least as far as she was concerned. So, every day, we had to make our beds, clean the house, and make our lunches before we left for school. The whole place had to be spotless. And then, on Saturdays, we weren’t allowed to leave the house until lunchtime. Every blinking Saturday, we had to spring clean the house, mow the lawns. That meant that by the time we got to be young adults, we all could work hard.

I was taught from the get-go the importance and value of being independent and working hard and earning your keep and all that sort of stuff. So that was one dimension of it. On the education side, I’m reasonably cognitively strong, so I never found it particularly difficult to read or do the maths and everything. But I was a bit of a haututū. I was bored a lot and got in trouble at school. I ended up with good grades, but I wasn’t particularly attracted to an academic career.

Most people in Porirua were factory people. So was I, from the time I was a teenager all the way through, working in the factories of Todd Motors and the like, surrounded by my cousins and my mates.

But then I went on my mission and got exposed to a different set of circles of what’s possible, and I got a vision for something better, something different, something more. When I got home, I ended up marrying reasonably young, but decided I needed to study. It took me six years to get my first degree.

My wife was an analyst programmer at the time, and she could earn way more than me, so in my final year of study, I said to her: “Look, dear, I’ll stay home and look after the baby, finish my degree, and you go out and earn the money.” She said to me: “Helmut Modlik, I’ve prepared all my life to be a mother. You go and do your blimmin’ job and let me do mine.” I laughed and said: “All right, dear.” I got my instructions.

So, from the two most influential women in my life, I’ve been taught to work and bring home the bacon.

Another observation I’d make is that my middle name is Karewa. That’s from my mum’s little brother, Karewa, my uncle Bill or Kare. His name’s Karewa William, which is why his Pākehā friends called him Bill. Uncle Kare was my next-door neighbour, and after my dad left, he became my substitute dad.

He was a bit of an entrepreneur, always had an eye for an opportunity. All my life, I’m seeing my uncle improving his lot, initiating interesting projects, dabbling in a bit of property. He was a car dealer and various other things, and successfully so for the most part. So I got an eye for that myself and found I was pretty good at it. I discovered that if you work hard and pay the price to have some competence in your studies and in the work you do, there are plenty of opportunities out there.

By the time I got to the role I’m in now, I felt confident that I’d accumulated enough of those key elements that if I shared that with my people, there was a formula there for success — and that’s what it’s proven to be.

I forgot to mention that when I did my MBA, some years after my first degree, my thesis topic was new-venture success from a Māori perspective. My research question was: “Do traditional Māori values inhibit, enhance, or are they irrelevant to new venture success?”

What I wanted to know was, can I be a successful Māori businessman and entrepreneur as a Māori person, the way my old people raised me? Or do I have to put on a mask and pretend I’m somebody else?

I was pleased to find that all the values that our old people gave us to live by enhance the successful pursuit of economic endeavours. Our story has proven that that’s so.

Post-settlement, which your iwi opted to take when it was offered, I’ve noticed that you’re front-footing medical centres, building supplies, vocational training. These are ambitious goals. But you’ve tried to do it, or tried to encourage the iwi to do it your own way and not be reliant on others.

The thinking is simple. Covid had just hit, so we had a bit of space to do some serious thinking. Our aspiration, our mission, is to do what we can to enhance the wellbeing, prosperity and mana of our people — and our manuhiri, too, especially those who need it most. In our little iwi, all our people take manaakitanga seriously. Our old people drilled that into us as a vital part of our tikanga.

So what’s our strategy for how we do that? It didn’t take long to figure that out. We’ll lift where we stand. We’ll start with ourselves. We’ll build what we need, and we’ll accumulate evidence for the competence and efficacy of doing that. We’ll partner with those who share our values and vision, and as we get better at it, well, we can do more of it.

So, that was basically our strategy, to paddle our own waka. And, to be honest, I used to get enjoyment out of saying to public servants, chief executives and politicians: “Whānau, we appreciate working with you, but we don’t rely on any of you fullas doing your jobs well enough to help us achieve our mission, because we have no experience of you fullas doing your job well enough to achieve that. We welcome you surprising us. We invite you to prove us wrong.”

So far, no one has surprised or proven me wrong.

There’s a little bit of reverse psychology there but mostly it’s because they’re systemically not in a position to be able to make the changes needed. And so, by focusing on ourselves, we’ve ended up building up our own rangatiratanga, our own mana motuhake capacity to look after ourselves and to look after our manuhiri. And it’s just continued to grow. And I think that’s the right formula for all our people.

And so do I. All the social indicators that we’re exposed to in the media predominantly point to Māori disadvantage. What do you see as our advantages?

What a great question. First and foremost is our whakapapa, and all that comes with that.

I’ve spent quite a bit of time in my personal and professional life thinking about what it is that our old people left to us — those taonga tuku iho that come down to us from them. Their worldview and their values sustained them for the better part of 1,000 years in these islands alone.

And one of the things that I think, and I got this thought from Whatarangi Winiata, is that for our old people, the circumstances of their life required them to be superb observers. Because, if they failed to correctly assess cause and effect in their world, they could end up making mistakes that were fatal. These were decisions on how best to deal with the material world, to deal with each other, to deal with the unseen world, and so on. Their survival was a consequence of careful and acute observation of those causes and effects, over many generations.

In general terms, those ideas have come down to us. The question is how to apply those observations in our day. And the main thing I would say is that westerners have a relatively narrow orientation of what constitutes a good life. And it’s tended toward materialism. It’s tended toward individualism. It’s tended towards consumption. And what has that brought us? It has degraded our environment and our world. Isolated our peoples.

But if you think about it, all the remedies for those things were with us the whole time, if we’d just had the wisdom to apply them. Our old people taught us how to look after our taiao and our people. What I’ve found is that those same ideas are similarly enriching and valuable in all settings: commerce, health, education.

The tikanga of our tūpuna is our secret sauce, bro.

Have we set the stage well enough for those who will follow in our footsteps?

That’s a good question. I can’t say that I have, but I know others have done a great job. I just mentioned one fulla who’s a legend in his own time: Whatarangi Winiata. Turoa Royal is another. They had the wisdom and the kaha to pursue the establishment of Te Wānanga o Raukawa, with others, to create a puna of wisdom and continuity of those mātauranga. So while we could have done more and better, I feel that the platform has been laid and there is more than enough in play now to push on.

I’m really pleased to kōrero with you, Helmut. I always leave a little bit of room for what else you do, because we often speak about mahi but not so much about things we love. I know you’re a proud family man, but is there something you do to keep yourself invigorated and enthused for the mahi that you do?

I was a lifelong player of basketball and I played up till I was 60 with my nephews, and then I got sick of being useless. So I’ve had enough of that, plus nobody plays defence any more, they just want to jack up three-pointers. I got hōhā with that. So I’ve been on the lookout for the last couple of years for something to keep me physically fit. I work out on most days, so I keep myself healthy, but I am looking for something a bit more fun that I can do physically.

I’m also an avid reader. I read voraciously. I always have since I was a little kid. And, of course, it’s whānau, bro. I have 13 mokos. I grew up in a place where everybody, as far as the eye could see, was my uncle, aunty or cousin. And that’s the best way to grow up. It’s the best way to live. Those things are where I get the rest of my juice from at this stage of my life.

What books should we all read? Are there some that have really hit you?

Depends on what rows your boat. When it comes to fast-food reading, that’s novels. I read all sorts of novels. My favourite fiction of all time is James Clavell’s Shogun. It’s a mind-boggling book of intrigue, and a wonderful story.

I’ll read all sorts of Jack Reacher-type books, but those are all comic book style for on aeroplanes and holidays, lying on beaches. I also read nonfiction that catches my interest, especially self-improvement, autobiographies, that sort of thing.

Give us a couple of titles that I can suggest to our readers to get hold of.

Well, okay. There were a couple of books that were crossroads books for me. One was As a Man Thinketh. It’s a tiny little book by James Allen. It was basically the idea that reinforced for me that we all think we see the world as it is, but the truth is, we can only see it as we are. And so, the question then becomes: Who are you and what’s in your head and heart? That was a powerful book for me as a young man.

Another one I read about 20 years ago was by American Stephen Covey, The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People.

Another one just jumped into my head. How to Win Friends and Influence People. By Dale Carnegie. There’s a classic. I read it when I went on my mission. If you read those three books, I can guarantee you’ll be a better woman or man after doing so.

(This interview has been edited for length and clarity.)

Helmut Modlik completed an MBA in 1992 before becoming the inaugural CEO of the Poutama Trust. He has headed Telco Technology Services, Connexis, and Patients First (Health Tech Solutions) and directed the masters of management programme at Te Wānanga o Raukawa. Before becoming CEO of Te Rūnanga o Ngāti Toa Rangatira, he was the MD of management consultancy Arrus Knoble Developments.