This article was first published by RNZ.

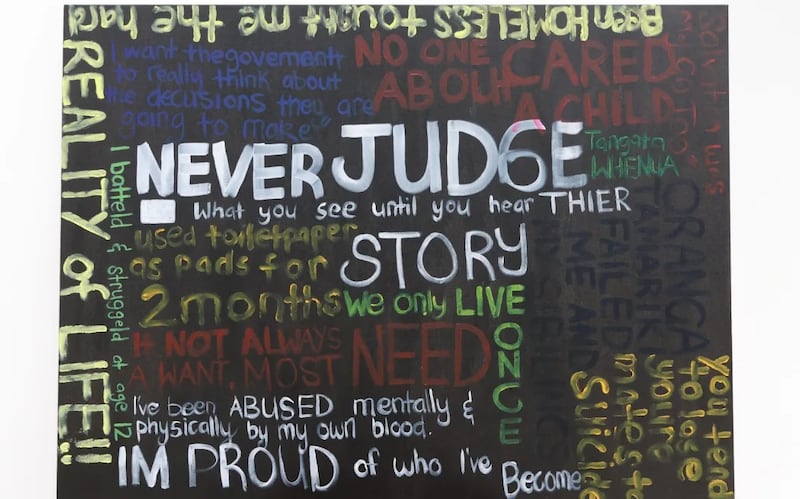

An Auckland-based youth homeless collective is calling on the government to make young people a priority and says more research must be done to tackle the issue of youth homelessness in Aotearoa.

In 2023, Manaaki Rangatahi called on all political parties to advance six key calls to action including guaranteeing the right to a healthy home, investment in youth housing, a comprehensive youth homeless strategy and better data collection.

Doing so would be a significant step in ending youth homelessness, Manaaki Rangatahi said.

Manaaki Rangatahi pou arahi (CEO) Bianca Johanson told RNZ that since the coalition government came into power, they have asked to meet with the housing minister but have been unsuccessful.

“We have not been able to get a meeting with Chris Bishop.”

A spokesperson for the minister confirmed to RNZ that Bishop had received a request for a hui, but he “simply isn’t able to meet with everyone who requests a meeting”.

Johanson said they had also not been able to meet with Minister of Child Poverty Reduction Louise Upston.

“Many of our ministers have not been briefed by those of us working within the sector and involved in research and the calls to action.”

Johanson said it was “super difficult” for the government to understand the complexity of the problem without them all sitting in one room.

“How are they really going to know about youth housing and youth homelessness?”

Johanson said Manaaki Rangatahi recently met with Tama Potaka as associate minister of housing, and minister responsible for responding to homelessness and told him that he has an obligation to implement policy changes and advocate for rangatahi.

“Some of the kōrero we received was that he is not in charge of the budget.”

Johanson acknowledged this but said ministers should still leverage the power that they do have.

“We need our ministers and the government to say rangatahi are a priority. We need people to actually explain why our rangatahi matter, because our rangatahi matter.”

Johanson said there were many policy, systemic, and structural changes across all the systems that rangatahi engaged with that needed to happen.

“If our rangatahi are failing, we are failing as a country, especially when it comes to the area of homelessness and housing.”

One of Manaaki Rangatahi’s calls to action includes a request for a duty to assist legislation.

“The duty to assist legislation would mean no young person can be exited from homelessness into nothing, so that’s from care, prison, mental health institutions, etc.”

The United Kingdom and Ireland have successful housing legislation, Johanson said.

“It makes a dent across the whole system and means rangatahi will be picked up within those systems and that people are actually legislated to care and do something.

“Because a lot of our rangatahi that have care and guardianship orders on them are on Queen Street right now, they’re in Auckland CBD walking around, rough sleeping.”

She said rangatahi needed bespoke, curated spaces in the form of supported youth housing.

“Rangatahi shouldn’t be just dumped in the house and left to it, because that is what we have seen in emergency housing, and then they walk away from those spaces because they’re unsafe, they’re very lonely.

“It’s vital to highlight the importance of what happens when our rangatahi go from facing housing insecurity, to how they actually fall through the gaps in the system.”

How bad is youth homelessness in Aotearoa?

In 2022, Manaaki Rangatahi collaborated with Ngā Wai a Te Tūī researchers Jacqueline Paul and Maia Ratana and released a research report which “exposed a severe lack of reliable data, services, resources, and funding targeting youth homelessness”.

It found that rangatahi and tamariki Māori experienced some of the worst housing deprivation in Aotearoa, and that there was no doubt that homelessness was a result of structural issues.

“Homelessness for Māori is attributed to colonisation and historical events that have destabilised Māori systems and kinship structures,” the report said.

Johanson said kaupapa and rangatahi Māori-led research into homelessness was “decades overdue”.

“We have been waiting for data and research that is kaupapa Māori-led, that shines a light on the exhausting and painful human rights issue that is our rangatahi having nowhere to go that is safe, warm, and provides manaakitanga.”

Johanson said the numbers of youth who were homeless in Aotearoa remained high but they currently do not have enough data to know “what is really going on”.

“That should be the government’s responsibility, to act, to give data.”

Johanson said the government had research funding for that purpose.

“If we don’t get government funding for anything that we do, yet we help and support the rangatahi of Aotearoa, then at least fund some amazing national research on what the data is.”

This research should be kaupapa Māori research that was holistic, indigenous and considered qualitative and quantitative information, Johanson said.

Minister responds

In a statement to RNZ, Potaka said he met Manaaki Rangatahi in September.

“I appreciated their insights, along with those of other stakeholders, and note the Ministry for Social Development has been working with Manaaki Rangatahi since the latter was first created.”

He said homelessness and youth homelessness had various root causes, and the government was working to address them.

“This includes our work to rebuild the economy to help create more jobs and get more people into work, coupled with work in areas of housing, emergency housing, cracking down on criminals who supply our communities with drugs, social welfare, mental health, and education.”

Potaka said no one, especially young people, should experience homelessness.

“I am committed to continuing to address the problem, and I am pleased with the work our government is doing to fast-track whānau with tamariki out of emergency housing and into more permanent housing through Priority One.”

Additionally, a spokesperson for the minister’s office said specific services were available to young people, including the Ministry of Housing and Urban Development’s transitional housing programmes.

“Wrap-around support is provided for people, including those exiting emergency housing, typically for around 12 weeks.”

They said the Ministry of Social Development’s youth service offered support for young people aged 16-19 who experienced significant family breakdowns or had high needs, assisting them in finding long-term housing options.

The government’s aim was to reduce the use of emergency housing by 75 percent by 2030, the spokesperson said.

“We want to make sure that emergency housing is used for its original intent - as a last resort used for short periods.”

- RNZ