This article was first published by RNZ.

Whakataukī (Māori proverbs) are a fun and powerful way to help rangatahi develop their own voices and find grounding in the “continuum of whakapapa”, Dr Hinemoa Elder says.

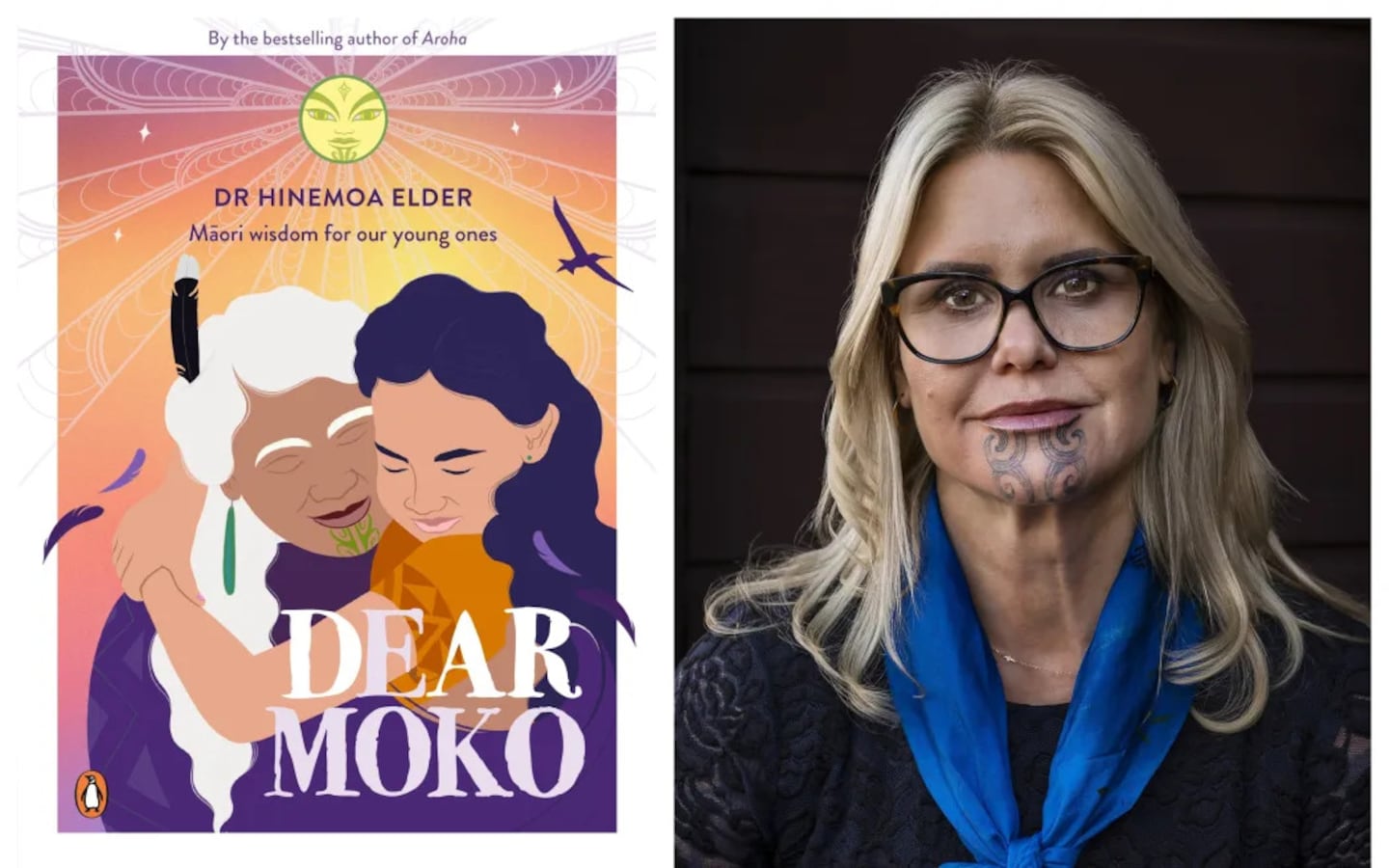

The child psychiatrist and author weaves observations from her professional life into the new book Dear Moko - a child-centred reshaping of her beloved 2020 whakataukī collection.

The idea that children should be “seen and not heard” - first introduced to Aotearoa by Pākehā settlers - is one that Elder challenges in Dear Moko.

Although this “older, more colonised” message about the place of young people still prevails in New Zealand culture, it is critical that whānau seek to understand young people’s actual lived experience, she says, as they did in generations past.

“I’m constantly trying to tune into a tūpuna [ancestral] voice in thinking about their struggles and trying to retain at least some of the older kōrero.”

Most young people are just trying to please their families, she says, and are “exquisitely attuned” to how their whānau receives them.

“I’m often saying to parents ‘Hey, our teenagers, our rangatahi get a bit of a bad rap but actually they’re very caring because they’ve been keeping their pain private in order to protect your feelings and they pay a big price for that’.”

As both a child psychiatrist and whānau advocate, Elder sees Māori around New Zealand facing “very serious challenges” when it comes to mental health, particularly in under-served rural areas.

“I’m really quite shocked about the degree of complexity and the amount of difficulty that our whānau are trying to absorb themselves without professional help at all.

“We need to make sure that rural communities are better resourced with mental health services and these services are functioning as well as looking at prevention.”

To be effective, mental health services need to take into account the cultural identity of the people they seek to support, she says, who often lack trust in the medical system.

“Our people have had bad experiences with health services. Very commonly they are sceptical and perhaps distrusting of what health services are actually about and what they might be offered.

“We have to do a lot of work to actually build that trust and a sense of safety and then we can start to do what you might call the therapeutic approach and that sort of work.”

Both published literature and practice-based evidence show that culturally informed approaches to Māori mental health and well-being are the most beneficial, Elder says.

“If we ignore that, if we don’t address that and actually utilise those resources, we’re missing out on a whole raft of rich, powerful tools that we can employ and help people connect with themselves.”

- RNZ