Inside our wallets and pockets lays a piece of Rotorua and Te Arawa history. For the past 20 years, revered ancestor Pūkaki has ventured across the motu on the 20 cent coin. Local Democracy Reporting’s Laura Smith explores his story.

The image of Pūkaki is etched on to the silver coin in intricate detail.

In the renowned Ngāti Whakaue rangatira’s arms are his sons, Wharengaro and Rangitākuku. His wife Ngāpuia (Tūhourangi) can be glimpsed between his legs.

The depiction is based on a well-loved and well-travelled carving of Pūkaki.

In storage since 2016, a decision is expected this year about Pūkaki’s next home.

In his temporary housing while Rotorua Museum - Te Whare Taonga o Te Arawa is closed for renovations, the carving dwarfs Pūkaki Trust trustee Professor Paora Tapsell.

The author, historian, and former Rotorua Museum curator and director shared the chief’s story with Local Democracy Reporting under his ancestor’s watchful eye.

A leader is born

In about 1700, Pūkaki was born on Lake Rotorua’s Mokoia Island, a refuge in a time of constant tribal conflict for his tribe, Ngāti Whakaue.

“Pretty much every season after the kumara was harvested someone would turn up on the horizon looking to attack us,” Tapsell said.

The iwi was envied for its geothermal resources, which warmed homes and negated the need for firewood, providing extra time for carving and weaving.

These were important for making peace with other iwi, through marriage and gifted taonga.

Pūkaki’s birth established peace between Ngāti Whakaue and Ngāti Pikiao, and his marriage to Ōhinemutu’s Ngāpuia was strategic. In times of peace, Pūkaki based his family at his father’s pā, Parawai, west of Lake Rotorua.

Pūkaki became a respected chief. Two of his sons, Wharengaro and Rangitākuku, led Ngāti Whakaue in his name against Tūhourangi, and forced them back to Tarawera.

The Pukeroa-Oruawhata area, the modern-day central city, came into Ngāti Whakaue control and Ōhinemutu became its base.

Pūkaki died soon after.

In 1836 his grandson, Taupua Te Whanoa, carved the rangatira from a tōtara log, fetched from the Ngongotahā stream.

The carving of Pūkaki towered over Ōhinemutu as part of a 5m kuwaha (gateway) on Pukeroa Hill, later being cut down to the tiki (statue) we recognise today.

A symbol of trust

Come 1877, the Crown planned to set up a tourist spa town in Rotorua.

Ngāti Whakaue wished to retain its land and under missionary-trained leadership chose to not fight the Crown but to form a union for protection and income.

Tapsell explained it was not as though the iwi could give a daughter to the Crown, but they could gift their treasured Pūkaki tiki as a symbol of trust.

And so they did, to Judge Francis Fenton of the Native Land Court, when he came for initial discussions that led to an agreement to establish the Rotorua township, with Ngāti Whakaue retaining ownership.

The agreement was fraught with issues in the decades to come – not least the Crown’s compulsory purchase of the township lands – but almost immediately, the trust symbolised by Pūkaki was disregarded.

Tapsell said within 10 days, Fenton, aided by Justice Thomas Gillies, presented Pūkaki to the Auckland Museum as their own personal gift.

Why Pūkaki travelled the world - and how he returned home

For about a century, the carving sat as a museum artefact, most of Ngāti Whakaue unaware he was there.

In about 1984 he came out of obscurity and into the global spotlight as part of the Te Māori exhibition that toured the US for two years.

“It was through Te Māori that Ngāti Whakaue were reunited with Pūkaki and another Ōhinemutu gateway, Tiki. He too had been gifted some seven years after Pūkaki as yet another reminder to the Crown of its solemn promise to uphold the Rotorua Township Agreement,” Tapsell said.

When Ngāti Whakaue elder Hamuera Taiporutu Mitchell joined the Te Māori tour in St Louis, he became upset when told Auckland Museum understood Ngāti Whakaue had sold – not gifted – their taonga.

Mitchell’s emotion at hearing this would prompt a mission to seek the truth.

Pūkaki returned to Auckland in 1987, and in 1994, Tapsell – Rotorua Museum curator at the time – resigned and began his Master of Arts thesis.

He researched Pūkaki’s origins, through kōrero with Mitchell, Archives New Zealand and in the Auckland Museum archives.

“We are really fortunate records were kept.

“Through the Crown’s own evidence, a diary entry by Judge Fenton’s interpreter, Captain Gilbert Mair, noted Pūkaki was gifted with great ceremony to Crown representative, Judge Fenton, symbolising Ngāti Whakaue’s permission to proceed with the formation of the Rotorua township,” Tapsell said.

On October 2, 1997 – 120 years after his gifting was initiated – Auckland Museum representatives were invited to a hui on Pūkaki’s home marae – Te Papaiōuru in Ōhinemutu – to discuss his future.

“Well, the Auckland Museum did more than that.”

Home, at last

Bringing Pūkaki back to his marae was a highlight of Tapsell’s life.

He was part of the group welcomed onto Ōrākei Marae the day before hundreds gathered to watch a crated Pūkaki transferred from the museum to Malcolm Short’s old truck for the journey south.

Ngāti Whātua performed karakia to see him home safe, and supplied eight mattresses as his bed.

Hundreds more people received Pūkaki home to Ōhinemutu, where the original gifting was finally completed as Governor-General Sir Michael Hardie Boys received him on behalf of the Crown and people of New Zealand.

The Crown and Ngāti Whakaue signed a memorandum of understanding and the Pūkaki Trust was established to ensure his safekeeping.

Mitchell was not at the ceremony, having died in 1994.

“His dying wish was that when Pūkaki comes home, he’ll be placed in the district council so he can eyeball everyone when they come to pay their rates,” Tapsell said.

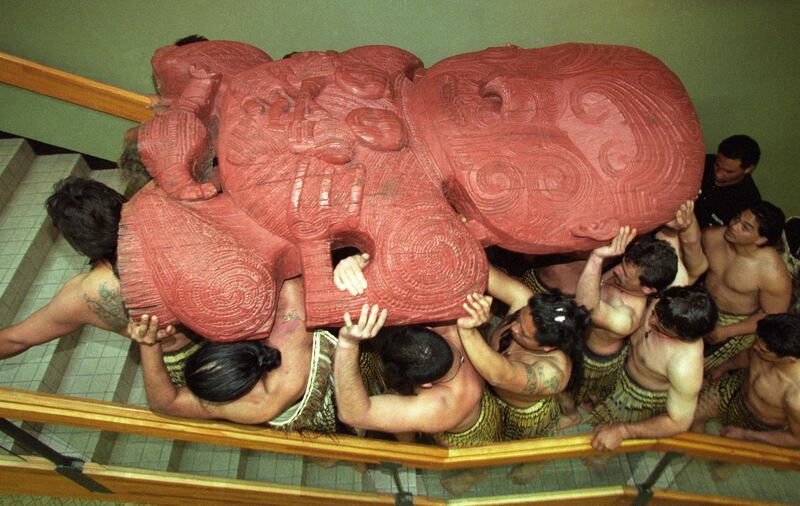

The 350kg carving was carried by descendants into the Rotorua Lakes Council building, where he stayed until 2010.

He was given a spruce up and in 2011 moved to the Rotorua Museum, which had conditions more suitable for his care.

The carving has been in storage since the museum closed for earthquake strengthening in 2016, but is accessible to descendants on request.

“He’s been around a long time.

“We’ll come and we’ll go, he’ll be watching.”

Tapsell said his future resting place would be determined this year.

“He’s here in good hands, but he needs to be amongst our people as well so that his lessons can be transferred.”

He is the trust’s Ngāti Whakaue representative, sitting alongside Rotorua MP Todd McClay, Mayor Tania Tapsell and Auckland War Memorial Museum representative David Reeves.

Tapsell said Pūkaki represented, “the old way of tapu and utu, reciprocity”.

This was every bit as critical now, as when he was first gifted in 1877, he said.

Tapsell said the trust had a deep responsibility.

“In a way it’s a burden, the obligations and the accountability, the duty I feel not only to Koro Hamu or Uncle Hapi but to Pūkaki himself and our people today.”

The Te Arawa leader in our pockets

The story how Pūkaki came to be on the 20 cent coin is not straightforward.

The Reserve Bank first minted the coins bearing his image in the millions in 1990.

As it was without Ngāti Whakaue knowledge, circulation stopped and the remaining coins were placed in a vault.

A new round of conversations with the bank began in 2002, when some of the 1990 coins began circulating again. This time, Ngāti Whakaue was able to endorse the use of Pūkaki’s image through an arrangement with the Reserve Bank.

Two specially minted gold coins were set aside and into which the tapu of Pūkaki was ritually transferred by Reverand Wihapi Winiata, clearing the way for all future Pūkaki minted coins to circulate free of any ancestral restriction.

One represented the Crown, the other Ngāti Whakaue–Te Arawa.

“So that whenever our people pulled out that 20 cent coin, they’ll feel safe to spend it,” Tapsell said.

“But at the same time, they know it’s part of their identity. It’s who we are and its our gift to the Crown … Pūkaki belongs to the people of New Zealand.”

Winiata, original trustee and Ngāti Whakaue leader who Tapsell succeeded on the trust, said at the time, “The Pūkaki coin symbolises the future and the promises the treaty holds for us all. We are two sides of the same coin.

“By respecting what makes us unique, Crown and Māori working together side by side, just imagine what a wonderful country New Zealand will be.”

LDR is local body journalism co-funded by RNZ and NZ On Air.