Whispers from the Colonised Windows of Palestine and Aotearoa merge two distant yet connected cultures in an expression of grief, resilience, and hope.

The mini-festival explores the struggles of colonisation between Palestine and Aotearoa.

The showcase is part of the Wellington Fringe Festival and will be on 14-18 of February at two/fiftyseven in Welling.

Te Ao Māori News spoke to three of the artists.

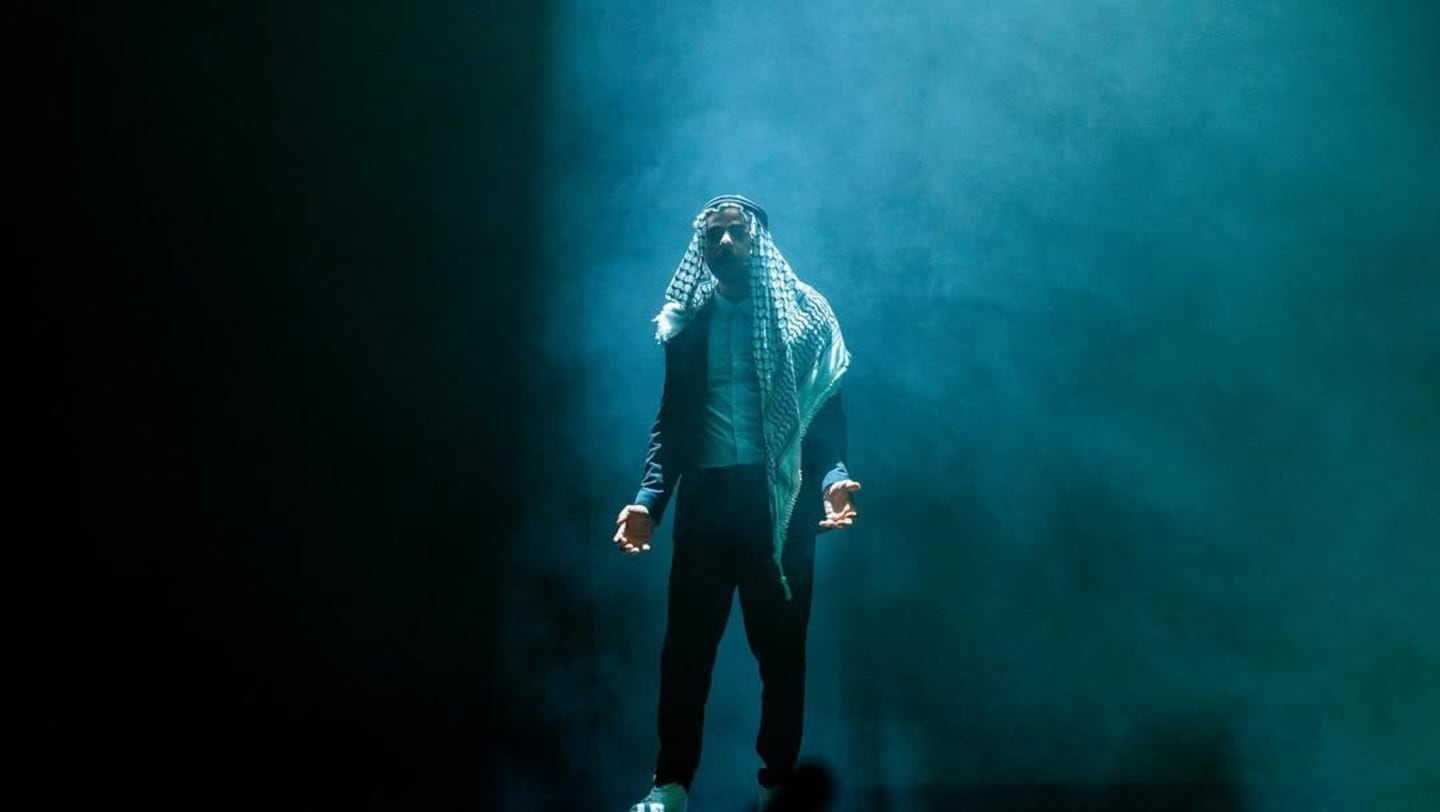

Dr. Sameh Shamout is from Tubas in the West Bank and is a lecturer of architecture at Unitec and founder of Erhasat, the organiser of this festival.

Shamout says, “This mini architectural festival is quite unique in its essence because it brings that living art component where we see the city, the house being built in front of your eyes and demolished and built again.”

“Every night I look at the roof of my room. I love it. I never imagined it would become my killer one day. It’s a disaster. If human beings have to fight one day this should never be repeated again - funding the carpet bombing of a city full of people, the mostly densely populated city,” says Shamout.

The festival also serves as an output of a research project, which was awarded the Unitec Early Career Research Funds and Excellence in Early Career Research 2025.

Shamout says he was very lucky to work with Tame Iti in different shows, with the last show being The Voices in the Shadows at the Aronui festival.

“When you bring Palestinian grief and Māori grief we did not need to plan anything, because it’s energy. It’s all about the vibration, that’s what Koro (Tame) says,” says Shamout.

Lee Stuart (Ngāti Pū, Ngāti Rangitihi) is a kaiwaiata, musician and singer.

Stuart’s first project alongside Shamout was called The Windows of Palestine.

“I always say with Sameh and I, it’s like our tupuna are always just linking up before us. It’s really important mahi for Māori and Palestinians to stand together,” says Stuart.

Katrina Mitchell-Kouttab is a Palestinian storyteller, actor, and writer.

Mitchell-Kouttab met Sameh through the Palestinian Community, describing that many were very supportive together towards each other during this conflict and genocide.

“We formed really strong connections and friendships with the tāngata whenua because it’s just a natural progression of Indigenous peoples,”

Art is a form of resistance. Telling your story is a very sacred way of ensuring that you are not erased, that your ancestors and still have a voice. In creating this art piece, we’re grieving, we’re exploring and we’re healing,” says Mitchell-Kouttab.

Mitchell-Kouttab says, “Many people don’t know the history of Palestine, just as they won’t know Māori history either because there is this intentional erasure. Palestinians were pulled out of their homes in 1948, and the State of Israel was created with the food left on their tables, with the stove still boiling hot soups or, with all their clothes in their wardrobe, their jewelry on the table, the children’s toys in their bedrooms.”

“They were pulled out just within a few minutes and told they were never coming back again and then a Jewish family moved in and took the food and finished it on the table and went through the house, looking through drawers,” says Mitchell-Kouttab.

The importance of pūrakau

Stuart echoed the importance of pūrākau, “it means so much to us as Māori and as Palestinians. Together the performance is about weaving old stories and new, and it’s about coming together because united, we are undefeatable.”

“I started this off by translating Palestinian songs that were in Arabic and translating those into te reo Māori and it was such a natural flow because of the themes they use, a lot of whakataukī and kiwaha,” says Stuart.

“Arabic is a beautiful language that sings and so is te reo Māori - it’s a language that sings and soars.

I have been on my haerenga reo Māori for the last couple of years and I’ve always maintained that te reo Māori is the language of resistance. And so, I wanted to find ways to use my reo to toitū te mana o Paretinia, especially through art," says Stuart.

Mitchell-Kouttab says, “I think Indigenous people just recognise each other. When we go to the rallies, or we just sit down and kōrero, sometimes we just look at each other’s eyes and we don’t have to say anything.

You just feel this incredible understanding and connection and acknowledgment and respect for each other, and I think that’s what’s missing in the world and it’s really beautiful that that’s being called upon and that’s starting to grow," says Mitchell-Kouttab.